Today in Cairo, Fatah, Hamas and the other main political factions in the occupied Palestinian territories announced a reconciliation agreement promising new democratic elections in Gaza and the West Bank “within a year”.(1) However, this development intersects with another timeline as Salam Fayyad’s two year ‘state building’ initiative comes to its conclusion in the West Bank, with a parallel plan underway to seek UN recognition for the ‘State of Palestine’ when the General Assembly reconvenes in September. Here, we attempt to consider the significance of this second deadline to the spatial struggle in Israel-Palestine.

Until recently, little direct attention had been paid to the statehood/recognition drive within the activist community. This is perhaps due to the fact that the politics and ‘institutions’ of the Palestinian Authority (PA), its vestiges of ‘prosthetic sovereignty’(2) under occupation, seem so disconnected from both the reality of the spatial struggle on the ground and the global civil society movement for Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) to hold Israel accountable for its ongoing violations.(3) However, as the deadline moves closer, it seems that an increasing number of commentators are beginning to agree on the potential significance of September, whether from the view of the implicit possibilities for empowering the Palestinian struggle,(4) (5) or the inherent dangers of pursuing such a course without territorial sovereignty or political unity,(6) (7) or simply of its likely failure and the possibility to move beyond the questionable logic of the ‘two-state solution’.(8)

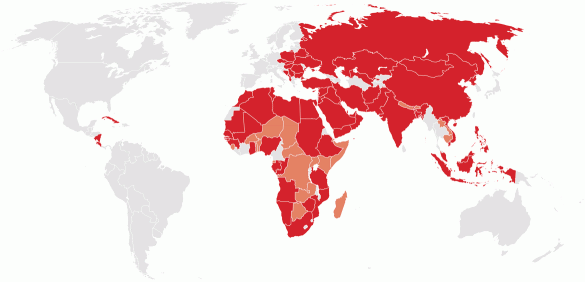

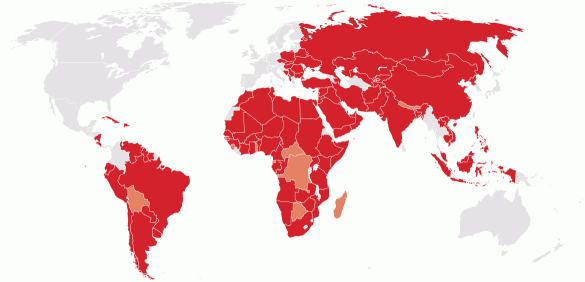

In light of several new countries (particularly in South America) officially recognising the ‘State of Palestine’ over the past six months, it has been argued that such a strategy for statehood/recognition could contribute to transforming the balance of power at a geopolitical level. Such a change, it is hoped, would open new legal and political channels through which to hold Israel accountable for its continuing military occupation and confiscation of Palestinian land, as well as historic injustices.

However, others have taken a more critical view of this strategy, considering it disingenuous or even delusional to be discussing ‘independence’ and ‘statehood’ at a time when Palestinian sovereignty and territorial contiguity are far from a reality, and that relying on international bodies to uphold international law in Israel-Palestine would be naïve considering their poor track record to date. It has also been argued that achieving Palestinian political unity is a far more pressing challenge and, indeed, it remains to be seen whether today’s developments signal the way towards a representative political body aligned with the wider Palestinian struggle.

Here, we offer excerpts from a handful of recent articles by activists and civil society commentators, outlining some of the main points of contention and discussion regarding the statehood/recognition drive.

Ali Abunimah of the Electronic Intifada cautions that the statehood drive represents a diversion from the broad-based demands of the BDS campaign:

Rather than fetishising “statehood”, the BDS campaign focuses on rights and realities: it calls for an end to Israel’s occupation and colonisation of all Arab lands conquered in 1967; full equality for Palestinian citizens of Israel; and respect for and implementation of the rights of Palestinian refugees. These demands are all fully consistent with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and international law.” (6)

Further, he argues that the statehood drive would achieve nothing tangible on the ground, whilst sidelining the struggle of Palestinians within Israel and refugees in the diaspora:

Recognition of a Palestinian “state” under Israeli occupation would certainly solidify and perpetuate the privileges and positions of unelected PA officials, while doing nothing to change the conditions or restore the rights of millions of Palestinians, not just in the territories occupied in the June 1967 war, but within Israel, and in the diaspora.

Far from increasing international pressure on Israel, it may even allow states that have utterly failed in their duty to hold Israel accountable to international law to wash their hands of the question of Palestine, under the mantra of “we recognised Palestine, what more do you want from us?” (6)

Jeff Halper of ICAHD contends with this view, arguing that civil society must seriously engage with the September deadline since it represents a political reality that cannot be ignored:

September is coming whether we are ready or not. Like it or not, we are part of a political process together with governments. That process, moreover, has a clear political goal: ending the Occupation and achieving a just peace between Israelis, Palestinians and their neighbors. I would argue with Ali that our ongoing campaigns and actions, from BDS, lobbying, international mobilization and pressing for the implementation of international law through resisting house demolitions and the displacement of Palestinians in Bil’in, Sheikh Jarrah, Silwan and the Jordan Valley, are important and must continue. But I don’t think they alone add up to a political force capable of ending the Occupation or of achieving a one-state solution. We are in a bad marriage with governments – the Palestinian Authority included. We the people can only bring the issue so far. We are not elected, have no defined constituencies, do not negotiate and cannot sign treaties or peace agreements. We alone cannot resolve the Palestine/Israel conflict. At some point we must pass the baton to governments. (4)

Issa Khalaf, academic and author on Palestinian politics, argues that the drive for UN membership need not be incompatible with the ongoing rights-focused struggle centred on the BDS movement:

The question is, must Palestinian strategy consist of either a state declaration or a non-violent campaign that demands freedom, human rights, and equality complemented by and contextualized in the boycott, divestment and sanctions movement?

My answer is a contingent no, especially now that negotiations are moribund and Abbas/Fayyad are not adhering to the US-Israeli scheme of coercing the Palestinian people into a settlement of surrender. Before explaining, let me say this: statehood declaration, as a goal by itself or embedded in a more inclusive strategic context as I will suggest, is dependent on one critical element: it is meaningless if not accompanied by de jure UN recognition/membership. (5)

Khalaf goes on to outline how such seemingly disparate strategies might in fact reinforce one another:

The Palestinians would develop a multifaceted strategy that includes three elements: seeking de jure UN membership, accepting in principle two states based on international law and UNSC resolutions, and struggling for freedom, human rights, equality in a non-violent campaign of resistance to end the occupation and that affirms peace, coexistence, and life. Each strategy will have its own constituent tactical elements (one at UN, the other peace conference/negotiations, the third mass organizing). Together they have a better chance of ending the occupation than the current state of collaboration with the occupiers in an interminable “peace process.” (5)

Those in international law circles have been debating the concept of Palestinian statehood for some time (see John Quigley “The Statehood of Palestine: International Law in the Middle East Conflict”). However, what has not been carefully examined is the ‘utility’ of legal recognition and its relationship with local and international grassroots movements. How can the theatre of global politics be squared with the seemingly incongruous realm inhabited by the grassroots activists coming face to face with Israeli bulldozers and teargas canisters on a daily basis?

As Khalaf argues, it would be imperative to square this circle, to form a synergy between political factions, activist groups and international civil society movements if this initiative is to become a meaningful tool for spatio-political transformation. Indeed without such an alignment we would almost certainly find ourselves in Abunimah’s scenario, with yet another false horizon undermining the momentum of the ongoing Palestinian struggle.

Regardless of whether international recognition of Palestine can change the spatial reality on the ground, it will undoubtedly transform dominant media narratives and wider public perceptions. And, as Halper cautions, if we do not engage with impending political realities, we will lose the possibility to have a hand in shaping their outcomes. Indeed, there are already malign efforts underway aimed at undermining the recognition of Palestine at a political level (9) and at crushing militarily the possibility of its actualisation as a sovereign entity on the ground (10). At this time of unprecedented change in the wider Arab world, not just revolution but also counter-revolution, it is imperative to create a space of critical engagement in which Palestinians can write the narrative of their own spatial future.

Bibliography

1. Ma’an News Agency Fatah, Hamas in unity govt ‘understanding’

2. For more information on the BDS movement and its demands, please refer to Introducing the BDS Movement on the campaign website

3. The term ‘prosthetic sovereignty’ was coined by Eyal Weizman in Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation to describe the illusiory Palestinian sovereignty under Israeli occupation instituted through the Oslo Accords.

4. Jeff Halper Mobilizing for September?

5. Issa Khalaf Two cheers for Palestinian statehood-recognition

6. Ali Abunimah Recognising Palestine?

7. Ahmad Samih Khalidi A West Bank anachronism

8. Yousef Munayyer Will a Palestinian Autumn follow an Arab Spring?

9. Ron Kampeas Jewish groups debate ways to thwart U.N. recognition of ‘Palestine’

10. Gill Hoffman ‘Annexation for declaration’ idea advancing in Knesset