By Daniel Monterescu

This article was originally published under the title “The ‘Housing Intifada’ and Its Aftermath: Ethno-Gentrification and the Politics of Communal Existence in Jaffa” in Anthropology News, December 2008, pg. 21.

(Republished on arenaofspeculation.org with permission from the author.)

Jaffa, an ethnically “mixed town” located minutes away from Tel-Aviv’s metropolitan center, yet marked as sui generis cultural and political alterity, is home to 20,000 Palestinian citizens of Israel. Struggling since 1948 to sustain viable collective existence, the Palestinian community makes up a third of Jaffa’s population and about 4% of Tel-Aviv’s metropolitan population. For the city and the state, Arab Jaffa has long presented a political “problem” resulting in recurrent strategies of containment, surveillance and control. Arab community members describe themselves as a “double minority” excluded at both national and municipal levels. Bereft of their old political leadership and with no stable middle class to speak of, they struggle for political recognition and affordable housing.

After decades of urban disinvestment, the Jaffa housing crisis reached its peak in the 1990s and became a symbol of Palestinian presence in the city. As Palestinians were faced with creeping gentrification and neoliberal municipal planning that promoted the commodification of lived space, a deep sense of unrest triggered the first signs of community mobilization. In 1995, within what came to be known as the “Housing Intifada” (Intifadat al-Sakan), 30 Palestinian families squatted in empty houses formally “owned” by the state, administered by the Amidar governmental housing company and designated for future private development. A state-sponsored plan for affordable housing put an end to the Housing Intifada and heralded the start of negotiations between Palestinian community leaders and municipal authorities.

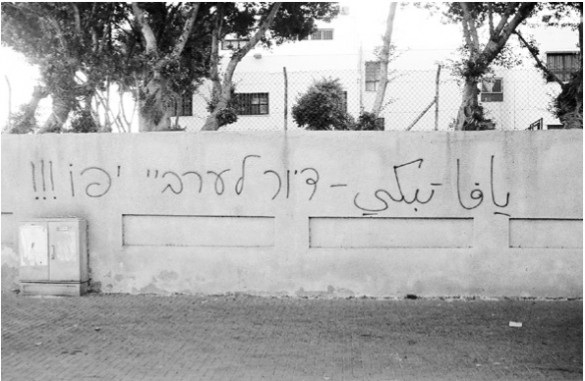

Such moments of collective action mark a shift from a liberal discourse of “coexistence” to an assertive claim for political entitlement and “collective existence” (Kiyan). The housing problem thus encapsulates a claim over the historicity of the city as well as a dire need for practical housing solutions for low-income families. Although Palestinian communal mobilization has been increasingly visible since the October 2000 Events and Al- Aqsa Intifada, it is no match for market forces that promote the Judaization of the city. The recent emergence of gated communities in Jaffa signals new modes of urban exclusion that reshape previous forms of spatial distinction. Reviving previous traumas of displacement, gentrification reshuffles communal and spatial boundaries, further destabilizing Palestinians’ sense of belonging. In 2007, the threat of “urban removal” disguised as “urban renewal” reached a new level when the Israel Land Administration issued 497 evacuation orders to Palestinian families charged with illegal construction. As these families all live in the `Ajami neighborhood, a hot spot of Jewish gentrification, it was interpreted as another attempt to “transfer” the Arab population out of Jaffa.

Beyond producing a deep sense of alienation, ethno-gentrification and Palestinian resistance to it push new social actors to the fore. Instead of the liberal plea for “equality,” a new discourse of urban rights calls to institute an inclusive redefinition of citizenship tailored for the “indigenous national minority,” which seeks to combat neoliberal urban restructuring. Increasingly visible NGOs like Shatil’s Mixed Cities Project, Adalah and the Popular Committee for Housing and Land in Jaffa are beginning to do precisely that. Today the struggle over the Palestinian “right to the city” continues in courts, media and through grassroots activism.

(Note: For more discussion on “The Right to the City” with regards to Palestinian citizens of Israel, please refer to the first volume of ‘Makan’ (the Journal for Land, Planning and Justice), shared on this site with kind permission from Adalah.)

Daniel Monterescu is assistant professor of urban anthropology at the Central European University in Budapest. He is editor (with Dan Rabinowitz) of Mixed Towns, Trapped Communities: Historical Narratives, Spatial Dynamics and Gender Relations in Jewish-Arab Mixed Towns in Israel/Palestine (2007).