by Darryl Li

This essay is based on a lecture delivered at the University of Palestine Law Faculty in Gaza, 2 July 2011. It was originally posted on Jadaliyya, and is re-posted on arenaofspeculation.org with permission from the author.

Darryl Li is a doctoral candidate in Anthropology and Middle Eastern Studies at Harvard University and serves on the editorial board of Middle East Report. You can follow him on Twitter at @abubanda.

For decades, the international law of occupation – a branch of the laws of war (or “international humanitarian law”) – has played a major role in structuring debates around Israel/Palestine. As applied to the West Bank and Gaza Strip, the law of occupation has provided a useful and globally shared set of criteria for analyzing Israel’s discriminatory and repressive policies, as well as certain Palestinian actions.

There is perhaps no legal document cited more frequently in debates on Israel/Palestine than the Fourth Geneva Convention, held up by many as a sacred pact of civilization enshrining basic standards of humanity in wartime. But as the impossibility of partition (the so-called “two-state solution”) as a viable way to end the conflict becomes ever-clearer, it is long past time to grapple with how the law of occupation can also hamper collective thinking and action.

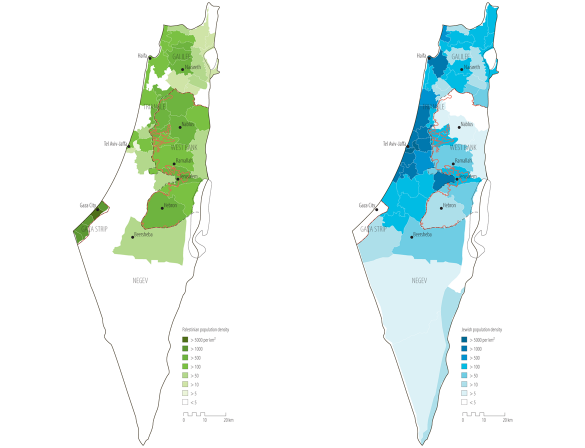

For over forty years, ten million people between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea have lived under a single segregated political regime – the State of Israel. Occupation law is not merely an inadequate tool for analyzing this regime; it can also help legitimize the very spatial arrangements upon which it depends.

A Law of Otherness

Since 1967, the international community has demanded that the Israel apply the law of occupation to the West Bank and Gaza Strip and has condemned its many violations of that law. The law of occupation – as embodied primarily in the Fourth Geneva Convention (1949) and the Hague Regulations (1907) – provides a set of standards governing a state’s conduct when, due to an armed conflict, it finds itself in control of territory other than its own. These standards are generally more detailed and theoretically more robust in enforcement than similar provisions in international human rights conventions. Designed to balance the security of the occupying power against the rights of the occupied population, they shape public debates by enunciating basic ground rules, such as the well-known prohibitions on torture, collective punishment, and destruction of property without military necessity. These rules impose duties on states; some of them also impose responsibility on individuals when violated (such violations are known as war crimes).

Since the eruption of the first intifada in 1987 placed the West Bank and Gaza Strip at the center of the Palestinian struggle, much of the diplomacy, activism, and scholarship related to the conflict has revolved around three questions: To what extent should the law of occupation apply? Do the acts of Israel or others comply with this framework? And how can this framework be implemented or enforced? Instead of revisiting these old debates, let us re-examine the assumptions behind the consensus position of the international community upon which Palestinians and their allies have relied.

Seizing territories in wartime is not illegal in itself, but modern international law forbids their unilateral annexation. Accordingly, the modern law of occupation treats these situations as temporary and seeks to preserve the status quo ante pending a conflict’s final resolution through a peace treaty or other political agreement. Consistent with this logic is the Fourth Geneva Convention’s absolute ban on colonizing occupied territories (“settlements”). This assumption of “temporariness” obviously falls apart in the Israel/Palestine case: not only because the occupation has continued for so long, but because it involves a state committed to the demographic transformation of these territories.

It is no secret that respect for occupation law in Israel/Palestine is in short supply. But it is important to draw attention to two crucial assumptions implicitly embedded in the demand to apply occupation law in this case, assumptions that themselves perform political work even when the demand itself is not heeded; assumptions whose consequences we must reckon with.

The first assumption is that the state of Israel is an international legal entity delineated by the “green line” boundary that existed until 1967, distinct from the West Bank and Gaza Strip.(1) The second is that the Israel at most owes the inhabitants of these territories a kind of basic normality: providing for their humanitarian needs and allowing normal commerce to the extent possible, but without any specific political relationship or responsibility to them. Unilateral annexation, and therefore citizenship, is off the table. Let us call these assumptions of otherness: otherness of the land, otherness of the people. Together, they reproduce the idea that the West Bank and Gaza Strip and their inhabitants are outside of, distinct from, not part of Israel.

Occupation law does not require either of these two propositions, but its widespread use as an analytical framework and normative model undeniably helps normalize them. The demand that Israel stop settlements or the separation barrier because occupation law says so cannot be easily separated from occupation law’s framing principles of temporariness and its assumptions of otherness. One reason why occupation law enjoys widespread appeal – why it can provide a shared language that Palestinian nationalists, liberal Zionists, and the “international community” alike can employ – is because its implementation would be consistent with the so-called “two-state solution” to the conflict. Indeed, in light of occupation law’s ban on colonization, one can argue that its implementation is crucial for ensuring the viability of any Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

Partitioning the Imagination

Occupation law’s assumptions of otherness, premised on a simple dichotomy between occupied territory and occupying states, are not particularly helpful in grasping a basic fact: since the 1967 War, the territory of the British Mandate of Palestine has been ruled by a single supreme authority. The green line has defined the state of Israel for less than one-third of its liftetime (1948-1967). Meanwhile, it has constructed a complex set of political, legal, economic, and social relationships that have essentially dissolved the West Bank as a coherent entity and converted the Gaza Strip into a large-scale holding pen for a quarter of the country’s indigenous population.

That this regime discriminates between its inhabitants is well-known, favoring Jews, whether they live inside the green line or outside of it, whether they are from the country or not. But equally important to maintaining this privilege is segregation amongst non-Jews, who are divided into various categories according to a spatial logic.(2) Those inside the green line may, at most, hold Israeli citizenship (ezrahut) with some formal rights, while lacking the true inclusion that comes with possessing Jewish nationality (leom). Next come residents of occupied Jerusalem, who have mobility without citizenship, followed by West Bank residents who have neither, and then finally Gazans at the bottom of the ladder. Refugees outside the state, of course, enjoy no share in this polity at all.

While the law of occupation does not require partition as a political solution, it does contribute to a partitioned understanding and analysis of this regime. Occupation law’s assumption of the otherness of the occupied territory encourages us to treat pre-1967 Israel as a given while limiting attention to settlements and various repressive practices only as so many different “violations.” Even when such violations are treated as systematic, they are detached from the larger context. They focus solely on only the twenty-two percent of the country comprised of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, leaving parallel situations inside the green line to be analyzed separately as “domestic” problems under international human rights law.

At the same time, the otherness of the occupied population is not only unquestioned and left to the realm of “political negotiations,” it is also a crucial feature of this regime. Israel persists in the notion that there is a Jewish and democratic majority inside the state, even as the state’s refusal to define its boundaries renders the very idea of “insideness” inherently unstable. Annexing the territories and their populations would destroy this illusion. Thus, occupation law, with its concomitant strictures against annexation, is a useful legal placeholder once divested of any real ability to constrain colonization. Contrary to what some may believe, Israel has never rejected occupation law wholesale; right-wing ideologues may assail it as some kind of security threat, but Israel’s military lawyers and courts continue to selectively rely on occupation law when it suits their purposes.

This is also why partisans of Israel display incredible bad faith when they rhetorically demand to know why Tibet, Kashmir, or Chechnya are not considered occupied territories. China, India, and Russia may be just as or even more repressive than Israel, but they at least extend citizenship to the populations involved and pretend to accept their equality. And that is the last thing Israel wants to do. Occupation law may make many demands on a state to respect certain basic rights of civilians. But the one thing that it does not demand – and that it never could demand – is the extension of equal citizenship to occupied populations.

Sovereign Voids and Native Administration

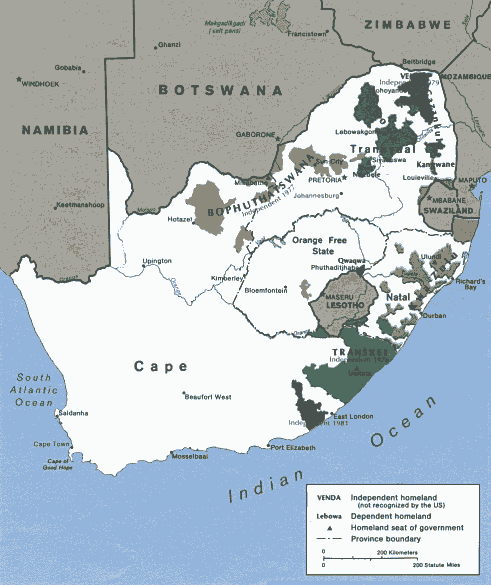

The segregated regime described above is constantly evolving through “facts on the ground” that reshape lived space, such as the separation barrier, checkpoints and roadblocks, and new roads and colonies. In order to clarify how occupation law’s basic assumptions can facilitate this process, let us compare Israel’s policies towards native self-administration with the South African Bantustan experiment.

For the better part of the last two decades, Israel has relied for native management in significant part on the Palestinian National Authority (PNA), a self-rule body that exists in dozens of disconnected enclaves run by Fatah in the West Bank and Hamas in the Gaza Strip. The PNA has been widely criticized for legitimizing and extending the occupation: it assumes the burden of caring for natives, while Israel maintains the ultimate ability to dictate their conditions of life while colonizing as it wishes. Israel maximizes its control while minimizing its responsibility. At the same time, the Palestinians are stuck with maximum responsibility and minimum control: they are expected to “crack down on terrorism” in the absence of any political solution or sufficient rudiments of statehood.

Many critics have compared the PNA to the Bantustans in South Africa. The apartheid regime sought to deflect international criticism of white minority rule by concentrating much of the native population into disconnected patches of territory, and then declaring them to be independent sovereign states. Derisively called “Bantustans,” these enclaves were tiny, often non-contiguous, and entirely dependent on the apartheid regime, much like the PNA. However, the Bantustans largely failed to gain international recognition as states – although Israel and Taiwan supported them through security, political, and trade ties.

The scattered areas of PNA jurisdiction and the Bantustans may share many similarities, but there is a crucial difference from the standpoint of international law (to say nothing of their contrasting approaches to the problem of native labor). In South Africa, the state was attempting to alienate parts of its own sovereign territory and, more egregiously, to denationalize its own subjects. International law has spent so much time dealing with states claiming territory that it was unclear how it should even approach states trying to unilaterally rid themselves of territory, as South Africa attempted to do. It became apparent that the regime could not simply create “sovereign voids” in its own territory; it had to convince other states to step forward and affirmatively recognize the Bantustans as independent. Otherwise, the default option was that South Africa maintained its responsibility for those areas and their inhabitants, which is exactly what happened.

Israel/Palestine is different from the South Africa case. Thanks to occupation law’s assumption of otherness, classifying the Gaza Strip and West Bank as occupied territories means that by definition they were not part of Israel to begin with. Moreover, they have the unique status of already being “sovereign voids” in the sense that they did not transition from their status as colonial territories to belonging to any recognized nation-state.

From this starting point, it is far easier to relieve oneself of responsibility for resolving the political status of natives. South Africa faced widespread criticism for attempting to denationalize its own citizens. In contrast, Israel is not legally required to confer citizenship to occupied populations in the first place, or provide them with any political status whatsoever.

Territorially, South Africa needed states to recognize the Bantustans, and none did so. But in Israel/Palestine, we instead face the more ambiguous legal question of whether a territory is occupied, a question that turns on factual analysis instead of formal declarations. Israel’s 2005 “disengagement” from the Gaza Strip gave rise to a set of debates as to the status of the territory, even though it continued to exercise authority there through regular ground incursions, management of crucial infrastructure and administrative tasks, and control over borders and airspace. Although Israel did not convince the world that the occupation had ended, it created sufficient doubt and confusion to provide political cover for portraying its new relationship with the Gaza Strip as one of parity, between two neighboring states trading rocket and artillery fire. Israel reclassified the Gaza Strip from something like an occupied territory to a “hostile territory” with an even lower level of legal restraint. This helped legitimize a massive escalation of repression, including the tightening of the siege and the 2008-2009 onslaught.

In terms of legitimizing discrimination and conferring discretion to the state, Israel has achieved far more than the apartheid regime could have hoped to accomplish. But all of these rearrangements in the structure of the occupation have distracted from a much more important question. That is the question of why the people of Beit Hanoun in the northern Gaza Strip and Sderot in southern Israel should live as neighbors under the same supreme authority for over four decades, but with entirely different sets of rights.

Conclusion: At the Frontiers of Law

The purpose of this essay is not to attack occupation law, nor those who have devoted efforts to understanding and upholding it. The benefits and importance of this body of law are undeniable, and as someone who has worked over the past decade for various human rights groups on this issue I have no interest in repudiating it. But serious questions remain as to whether occupation law – historically developed and applied mainly around Europe (including parts of the Ottoman Empire such as Bosnia-Herzegovina and Egypt) – is an appropriate tool for facing the challenge of contemporary settler colonialism.

And this challenge is not merely a theoretical one. After decades of fruitless negotiations and unceasing colonization, there is a growing awareness of the limitations of partition in addressing the Israel/Palestine conflict. Some celebrate this as a step towards building a single non-colonial state for all of its citizens. Others mourn this development, either because they wish to preserve the Zionist project or because they fear that the demise of the partition option will only herald more bloodshed and suffering without respite. My point here is not to argue that the end of partition is a good thing or a bad thing. My point is that as partition recedes as a viable option, the evolving situation on the ground raises difficult legal questions that require sustained consideration.

Israel has skillfully deployed multiple juridical categories while physically reshaping the territories and populations under its control. Grappling with this situation requires more than reliance on static categories such as those of occupation law, or other approaches described as “apolitical” or technocratic. Instead, jurists, legal scholars, and activists would be well-served to also engage core questions of political belonging, responsibility, and equality in a manner that creatively engages the evolving spatial dynamics of this regime. In exploring the limitations and problems of occupation law, this essay is an attempt to join this difficult but necessary conversation.

End Notes

1. There are of course problems with treating the green line as an international boundary, but I think this is a reasonable statement of mainstream assumptions, for better or worse.

2. Discrimination between Jews is also important but beyond the scope of this essay, as are the rights of foreigners inside the Green Line.