by Ahmad Barclay and Dena Qaddumi

This article was originally published on Jadaliyya as a part of the recent roundtable in response to ‘Occupation Law and the One State Reality’ by Darryl Li, which was featured on this site last month. You can read the full roundtable on the Jadaliyya site, including contributions from Noura Erakat, Lisa Hajjar, Asli Bali and Nimer Sultany, and an afterword by Li.

As Darryl Li argues, occupation law has effectively masked the settler colonial origins of the Israeli state as well as encouraging a “partitioning of the imagination” whereby the Green Line divides “Israel” and “Palestine”. Allied with notions of a “temporary” occupation, this not only legitimises an ongoing colonization but also stifles creative, provocative action. As architects and urbanists, our approach is not only to critique the dominant spatial perceptions of Israel-Palestine but also to engage with modes of activism centred on a notion of “spatial resistance.”

While the production of spatial perceptions is significant in any context, it is in Israel-Palestine where the transformation of physical space, the consolidation of territory through maps and the translation of space into imagery have been particularly consequential. Further, perceptions are also shaped by a selective absence of information. In 2000, Edward Said described a “censorship of geography” – particularly in the US media – arguing that a lack of territorial context in “the most geographical of conflicts” had allowed the nature of the power relations to be distorted.

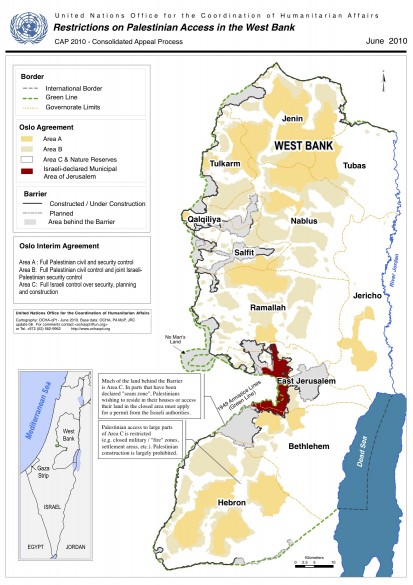

However, a sphere of advocacy has emerged in the last decade aiming to challenge this ‘censorship’. Specifically, it seeks to document Israel’s spatial control over the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Architect Eyal Weizman’s work with B’Tselem was instrumental in this regard, as they began a process of mapping settlements, checkpoints, restricted roads and the Separation Wall. This work has been subsequently developed and reified in the publications of UN-OCHA, which expanded the scope and detail of this mapping work.

While these maps offer a powerful image of Israel’s unilateral control over the West Bank and Gaza they also embed and perpetuate the trappings of occupation discourse. They present the West Bank and Gaza as discrete entities, whereby Israel is greyed out or omitted. Such a conceptualisation disembodies the spatial logic of the settlements – which function as suburbs of Tel-Aviv and Jerusalem – and separates them from “Judaisation” policies within Israel. Crucially, it also reinforces the notion of a Palestinian “national space” confined to the “occupied territories.”

Another problematic these images create is the perceived solidity of Israel’s “matrix of control.” A line on a map can emote a permanence that is not indicative of reality. The contours of Areas A, B and C in the West Bank are an example. These temporary lines – purportedly outlining a defunct Israeli withdrawal plan from the era of the Oslo Accords – have been etched into the Palestinian collective consciousness. Yet these lines have no legal validity or sanctity. The Israeli government operates within a much more fluid reality, continually shaped and re-shaped by ‘facts on the ground’, in which these lines are only one among many pseudo-legal mechanisms for legitimating continued colonization.

Combined, these preconceptions help to reinforce the idea of a truncated Palestinian geography and the perceived ‘absoluteness’ of Israeli power. In reality the physical manifestations of this power are more crude and ad-hoc than the map would have us believe. In actuality they are sustained through the continued threat of further dispossession and violence. Yet, as cleverly encapsulated in Suad Amiry’s Nothing to Lose But Your Life, it is possible to circumvent such physical and psychological obstacles, even if just as a means of survival.

The potentials for transformative agency are perhaps better revealed through an analysis which elevates human geography, rather than one which fetishizes territory, borders and mechanisms of control. Consider, for instance that more than a million Palestinians remain on the “west” of the Green Line and that the majority of Palestinian refugees – even those in Jordan, Lebanon and Syria – live within tens of kilometres of their historic sites of dispossession. From this perspective the obsession with drawing neat lines between a future Israel and Palestine is not only irreconcilable but irrelevant. Increasingly, initiatives throughout Israel-Palestine and beyond have attempted to break with this trajectory, expanding the scale of the struggle and shattering dominant spatial perceptions.

The organisers of TEDxRamallah, a recent cultural initiative that attempted to bridge this fragmented geography, describe how the notion of ‘Palestine’ acted as a key “common denominator”. They described the event as “a platform that brings forward the realization that Palestine is a topic that goes beyond a country occupied, and beyond a refugee stranded. It is one that starts apprehending the very essence of Palestinians and Palestine…since being Palestinian has no border or nationality.” Such a narrative underlines the possibility for Palestinian national aspirations to be defined in “universalist” terms of equality, rights and shared humanity, rather than simply mirroring the Zionist model of ethnic nationalism. It is also a means to re-energise a geographically fragmented Palestinian diaspora as a stakeholder and a strategic asset in the struggle for justice and self-determination.

On the ground, projects such as Riwaq’s 50 Villages transform the built environment to reconstitute a Palestinian civic space. Their strategy is one of collective participation, which harnesses the rehabilitation of historic village centres as a means for socio-economic development, and at the same time challenges the spatial restrictions of Oslo. This strengthens the notion of collective agency and reframes sites of occupation as potential sites of liberation.

In a different vein, DAAR (Decolonizing Architecture Art Residency) adopts the tools of architectural inquiry as a means to challenge and subvert the current spatial reality. In their early projects DAAR posed the question “How can Israeli settlements and military bases (the architecture of Israel’s colonization in Palestine) be reused, recycled or re-inhabited by Palestinians, at the moment that it is unplugged from the military/political powers that charge it?” Such a line of questioning explicitly undermines the notion of “facts on the ground,” as our conception of permanence is not just physical, but rather is informed by social and political meaning. Moreover, visually articulating the spatial possibilities for re-appropriating such material structures opens space for critical debate (what DAAR describe as an “arena of speculation”), neither constrained by nor entirely removed from present realities.

Following a collaboration with DAAR, Zochrot, an Israeli NGO, organised a workshop bringing together Palestinian and Jewish citizens of Israel with the aim of confronting the practical and pragmatic implications of planning the return of refugees. The processes, methodologies and assumptions in this exploratory initiative are explained in a segment of their periodical Sedek (A Journal on the Ongoing Nakba) entitled “Counter-Mapping Return”. Through the production of counter-maps, as a means to articulate shared space and alternative realities from those presented in the “official” maps, the workshop represents the beginnings of transforming imagined geographies into reality.

At the time such a workshop may have seemed fanciful, yet the events of 15 May 2011 seem to have dramatically shifted the horizon of possibility. As Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Gaza and the West Bank marched towards their villages of origin, we witnessed a collective agency, which directly challenged the notion of borders, the perceived solidity of maps, and the purported geographical scale of the struggle. It broke through longstanding psychological barriers and asserted the possibility for mass grassroots actions to transcend existing political processes.

We argue that it is in these forms of strategic activism – where weaknesses in the present power structures are exposed, and the lines between spatial intervention and critical imagining are blurred – that alternative spatial futures for Israel-Palestine will emerge.