Farhat Muhawi, Planning Director at Riwaq: Centre for Architectural Conservation

Abridged transcript of interview, recorded in Ramallah on Monday 7th September 2009

Farhat Muhawi (FM)

Ahmad Barclay (AB)

Tashy Endres (TE)

FM: I’ll start by giving you an overview of how Riwaq developed. Riwaq started in 1991 [by looking at] what we have. In the ‘Registry of Historic Buildings in Palestine’ we registered 50,320 buildings in 422 sites, which was a 10 year project that started in 1994, and ended with a big publication – of three volumes – in 2003.

This is how we started, knowing what we have in Palestine, because we never had a survey like this. Then we started doing conservation work, in villages and all around the West Bank – we can’t go in Gaza, but this is something else. We started doing conservation projects – especially in Ramallah because we were close – working with cultural institutions, with any organisation that is public in nature and wants to have a base. So we would bring in money and do the conservation projects with them. Up until now we have done something like one hundred projects all over [the West Bank]. This was the second stage of development.

The third phase was to talk about territory; to take the ‘historic centre’ rather than the building, and to work on the preservation of these. In Palestine we have more than 400 historic centres. From the registry, we decided we wanted to protect the most significant 50 villages, and that’s why the Biennale is about ’50 Villages’. We did some calculations, and decided that if we can protect these 50 sites, we will be protecting 50 percent of the historic buildings in Palestine, because these sites have the traditional fabric of the historic centre still in place. In many cases the centre is partially demolished, and many new buildings were built without planning.

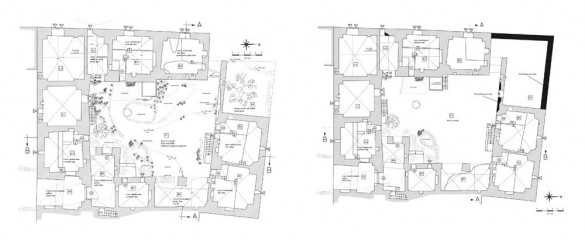

We took the historic centre of Birzeit as a pilot project. We are now working on three sites; Birzeit, Taybeh and Al Zahiryyeh in the south. But I would say the most important project of all is the Birzeit project. It is basically about how we want to bring life back to the historic centres in Palestine in rural areas; we are not talking about major cities and towns; the 50 sites are villages, because most financial resources and efforts in Palestine are going into cities. We are attempting to use the rehabilitation process in these historic centres as a tool for development of the local economy.

Of course this isn’t our only work, we also worked on a law for natural and cultural heritage protection in Palestine. We worked with the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. We did a lot of work with the Ministry of Local Government, because we don’t have an active Legislative Council – half of them are in prison because they are Hamas. That’s why this law was not ratified, so went through the [local government] ‘planning unit’, and we managed to pass a bylaw for the protection of historic centres. Until then, the only law that we had in Palestine was the “antiquity law” that protects only archaeological sites dating from before 1700. So, anything that is 100, 150, 200 or 300 years old is not an ‘antiquity’ and therefore was not protected by law.

We are trying to do this work without getting ‘experts’ from outside. We’re doing it, and we’re learning by doing it. The Birzeit project started in 2007, and now it’s moving, we’re learning. We did research into many things; socio-economic, architectural planning, legal, environmental research in the historic centre, but not only in the centre, because we see the centre as part of the town as a whole. Basically we have an equation between how we want to protect the historic centre and how to make it alive again. In the 21st century the standard of living is different to one hundred years ago, so we need to also consider that.

In Taybeh, we had a different scenario. We went into a negotiation process with owners, trying to convince them that we would do the conservation of the buildings from the outside, and that they could use the inside as they like. We managed also to do a very nice project there which was a preventive conservation for 60 buildings, and people now are doing the work from inside. The main challenge for rehabilitation is actually how to bring people to live in these areas; not how to use the buildings for public uses or services. For this we have different approaches; looking to buy buildings to make examples, because people don’t know how to re-inhabit them.

So, basically this is how we developed. We had conservation projects for historic buildings then we moved into looking at territory. Now we have another project, which is about how we are going to connect together these places that we have worked in. This is politics. So, we have worked in Taybeh and Birzeit, and several places around this path [north of Ramallah], so we decided to work through the Euromed Heritage Project, which we have been involved in.

As you know, the tourism sector is almost entirely controlled by the Israelis, and it’s based on religious monuments rather than on cultural tourism based around these historic centres and the traditional way people lived. So we are trying to make this connection, and the third day of the Biennale will be based around this trip to take people and discuss this trail that connects these. We also want to couple architectural heritage with existing activities in these places, for example we have the Oktoberfest in Taybeh, we have a heritage week in Birzeit, we have the apricot festival in Jifna near Birzeit. We are trying to build on these resources and to build an industry based on cultural alternative tourism. So, this is an element of the project of how to connect a part of the 50 villages, and trying to promote them to local people to make a market.

The most important thing about the rehabilitation, or the regeneration, is the question of how people will benefit. It is not just about protection of buildings. One of the ways is tourism; another was is cultural activities; another way is to work with the commercial strip and revitalise this, and another thing is to bring people to live back in these areas, because it is mostly abandoned. So this is the challenge, and these are the ways that we are trying to deal with it. We have worked with the community in Birzeit and we have a group there composed of owners, tenants, institutions, the municipality, that we meet with often. When we started the project we used to get five people, now we are getting fifty, because we realised many projects on the ground. They have seen that there is an intervention in their environment – it is getting better – and we gain the trust of people through that.

We see the 50 villages as a national cultural project. Using this potential, and working with communities there as a project that connects these sites which are currently divided by settlements and bypass roads. We are trying to offer [the Palestinian Authority] a national cultural project that is based on using the potentials of heritage to make these connections. One of the things that myself and Yazid [Anani] are proposing is to have a forest in Palestine that connects the villages. We are trying not to be political, by the way. We are doing this not because we want to be political, but because we see these potentials. The slogan is that we are “being political by being apolitical”. This is a national cultural project for Palestine, but the output also has to do with politics, because we are trying to build a connection that is not there.

TE: So, you have tried to introduce another logic?

FM: I gave a speech for the Biennale. I will read some of it for you:

“These fifty sites hold the basis for a national cultural pilot project. This project includes a vision for the future development of Palestinian rural spaces based on cultural heritage potentials. It also includes a web of endless connections between those rural spaces, forming another territory of spatial investigation called ‘spaces in between’.”

AB: One of the things that we’ve talked about with other people who we’ve visited is that everything seems to boil down to ‘Areas A, B, C’. However much you desire to make a masterplan, you always fall back to the fact that it’s much easier to build in particular areas; everything’s very fragmented; there’s not really a Palestinian spatial planning authority with any power. Does it become a case of planning outside of that framework, and then attempting to realising the projects within it?

FM: We try to work outside of this framework. The Oslo process was a real disaster; my thesis work was about that actually. My thesis title was “The Politics of Land Use and Zoning Under the Oslo Accords”. It was about how signing a political agreement can affect the people on the ground. How you divide the land; you say “A, B, C”; you have settlements; you have military bases; you have bypass roads; you have watchtowers. The landscape is full of images and elements of control, power, and surveillance. So this affected lives. You can do the disconnection easily; you can put a checkpoint any place. You have two roads which connect south to north, for example. You put five soldiers here and five soldiers there and you are talking about the lives of millions of people disconnected. Even sometimes in these towers you don’t have soldiers, but you always feel that there is somebody watching.

This system is based on trying to divide and control. The most important thing about it is that before, when the occupation was here [in the cities], they used to have to pay for the administration of these territories under international law. Now the Europeans are paying, through the PA, for the administration of these territories that are still under occupation. So, basically, I think [the Oslo Process] was a disaster.

AB: You said you are working outside of this framework?

FM: The “in between” is a project that we want to do. We have a dream; and we believe in this dream. It will happen. This is how Birzeit started. We never thought we were going to work on a historic centre as an NGO based in Ramallah, and to rehabilitate this centre; but now it is happening. We have infrastructure now; [we are starting] preventive conservation for fifty villages; we did several activities to make people start using the historic centres. On the commercial strip people started opening shops. All this equation, with more people coming to live in the historic centre can be a potential for tourism.

This is not an archaeological approach to historic centres; taking tourists to see ruins; that would not be what we want. We want to show the potentials of these spaces to local communities. If they can see the potentials of how things can happen, then they will take part because they own these places. We are going to start with five out of the 50 villages, in different places.

TE: It sounds like your approach is to start working on the ground; because if you wait of the Israelis to leave, then nothing will happen.

FM: Yes. It’s a case of just doing it. We have done the pilot projects and now, through the Biennale, we are going to go to everybody, to tell them that we want to help them. One of the things we are doing, for example, has an Arabic name meaning “think with us” (“Think-Net” we call it), bringing twenty internationals from different disciplines – artists, business people, anthropologists, architects, archaeologists – and sixty locals, to work with us on this rehabilitation and to think with us about what we are doing. We are already doing it, but we need help; you always need help.

There are many Italians that are coming to help us. There were two students that came from Ferrara last year, and they did a great job, and they are going to come during a training course before the Biennale for the trail project. We are trying to understand where to go. We do not know yet. We are discovering what we are doing. We are getting people from Germany, from France, from everywhere, who come and work with us for two or three months, depending on their programme. Everybody is welcome to take part in what we are doing, and Think-Net is a response to the fact that we have people and work, but we can still use help. This dialogue between local people and Think-Net and Riwaq is very important for the next year.

TE: With the pro-activity of your approach, it reminds me, and probably Ahmad also, of Salam Fayyad’s new plan for building a state within the next two years. It [seems to be about] changing the conversation. Not conversing with Israel endlessly, but saying that we will build a state on the ground. We will build institutions, and then people will not have an excuse anymore to not recognise us. It sounds a little bit like a cultural project like this would fit in very well with that.

FM: Everybody in Palestine was very involved in politics before – especially in the first Intifada – but when the Authority came, they were relatively corrupt. They didn’t have a plan for the future, and people became disinterested in what they were doing. I am one of those people. I don’t listen to [political] news anymore. I am concentrating on what I am doing, because I believe that this is a part of building the future of this country in a different way. Khalas (“enough”), we are going to do it! We don’t want to wait for the Authority, or anybody else, to do it. This is basically the equation.

Now, Fayyad is oriented towards business as far as I know, and I don’t think this is the right approach; but he is also [seems to be] oriented towards building infrastructure in rural areas rather than concentrating on big cities. This is as far as I know, but I think his plan has two dimensions. One is dangerous, which is trying to solve the whole problem through the private sector economy. The other part is going to rural areas and working on infrastructure, which seems to be about thinking for ourselves about how we want this country to be for the future. I agree with this part.

AB: You said something earlier suggesting that the political sphere is one of the partners in what you do. I wasn’t clear whether this was on a national level or a local one.

FM: We are basically working with municipalities rather than the government, partly because we have a bad relationship with the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. This is for several reasons. Firstly, they are trying to be powerful even though they are not. They don’t have sovereignty over the land – most archaeological sites are in Area C – so they say that they control this sphere, but on the ground they have no control. Our Authority is more oriented towards health issues and educational issues, and perhaps infrastructure, which is okay. These are the things that most of the budget goes towards, but not for heritage. They don’t see the potential in these places for the future of Palestine. Another thing is that since their mandate is for [antiquities], they cannot control what we are doing.

We [also] have the issue that we have a budget for projects that is more than the Authority. We have 15 people, and we work more than the 50 people that they have. So, basically, we have a situation with a weak government where NGOs are relatively powerful. NGOs are taking part of the role of government. It’s good and bad, but as a result we don’t have very good relations with them. But we do have good relations with the Ministry of Local Government, which is basically municipalities and the Higher Planning Council.

AB: What is the relationship between the Ministry of Local Governments and the PA? Is it still under the umbrella of the PA [like the Ministry of Antiquities]?

FM: Yes, but the specialisation is more towards planning and working with masterplans rather than working directly with sites of tourism and antiquity as the other ministry does. In terms of what Riwaq is doing, we are more close to the “Antiquities” than “Local Government”, but [our relationships do not reflect this].

TE: So the municipalities have a certain independence in how they can act, without the say-so of the PA always?

FM: They have their mandate under planning law. You have municipalities and village councils; you have what we call the ‘regional planning councils’; then you have the Higher Planning Council, which is under the Ministry of Local Government. ‘Regional’ in Palestine does not include the spaces in between. It means ‘Area A’, and this is how they see the vision, without seeing the connections or working on trying to understand the connections and how we want the future of this country to be. Basically, we believe in the municipalities. The Authority can do nothing at all. The municipalities have to be more powerful, because they understand their territory and resources better than someone who comes from outside.

We have 10,000 archaeological sites and features, and more than 50,000 historic buildings. The ministry alone cannot do this work. Us alone, we cannot do it. We have to work together.

TE: Right now, what can a municipality decide? What does the regional planning council decide?

FM: Municipalities are the main thing, because of the political situation. We have municipalities and we have village councils. Village councils must go to the regional authority to obtain permits. If you were going to plan an area, there is a procedure in the law that you have to publish it in the newspaper so that people can object. It then goes to the Higher Planning Council to decide. The municipality works on the planning of its own area; they put it on the wall, and people come to give their views on it. Then this is discussed in the regional planning council, and then it will be taken to the Higher Planning Council to decide whether to accept objections or not. This is the system. It was inherited from the British [Mandate] period.

TE: So the higher authority always has to give the okay?

FM: We are talking about planning. For building permits, in Area A you can build three storeys or five storeys high, and it’s down to the mandate of the municipality. To decide to change an area, [where] it involves land ownership and people [can] object, then it goes to the Higher Planning Council to decide, and when it’s decided the municipality takes care of realising the plan.

AB: Is this also true if there are no objections?

FM: Yes. It has to go there, because the final okay for the masterplan comes from there. For the detailed masterplan, the regional planning council decides.

AB: Do many municipalities have a permanent department employing masterplanners, figuring out infrastructure and areas for development? Or does it tend to be something that’s relatively ad-hoc based on individuals who want to build on the land that they own?

FM: In big cities – Bethlehem, Nablus, Ramallah – they commission people to do the masterplan. In other places it’s the Ministry that does the plan, because the villages don’t have the resources. They just have people who are not paid, who will come in the evenings and discuss planning issues.

The problem with our planning system is that they don’t respect the identity of the place. At Riwaq we talk about historic centres. It’s not just historic centres in masterplans; it’s about how we’re going to deal with the development of each area in the masterplan; to respect their identity and to develop these areas. But here it’s done by colouring a map, with certain laws for each colour; only that. The problem of the law, because of the political situation, is that the Ministry decided that in residential zones and commercial zones they have almost the same number of storeys. The only difference is with the percentage [of built area on site]. So, we don’t have an identity for a place.

Because of the scarcity of land, because of the occupation not allowing us to expand, they decided they wanted to allow people to build higher in all [planning zones], except in one which they call ‘Rivella’ – only a small area – where you can only build two and a half storeys. So it’s not about development and working with the identity of the space. It’s about building regulations which, because of the political situation, have become the same everywhere. You’ll have a neighbourhood where a lot of people own land, but you only have two or three that are building, and the rest are empty. So you don’t have an identity, a street like when you go to London. This is the situation when you look outside [in Ramallah].

Even though I don’t like the architecture in the [Israeli] settlements, they have some kind of identity that we don’t have. We used to have this in the historic centres, and in our architecture in the 1960s.

TE: If you say that we are lacking identity, what do you define as ‘identity’?

FM: (Laughs…) It’s not an easy issue, but I feel that, for example, in Ramallah, because of the scarcity of land and because the price of land is very high, everybody is building the same shape, the same number of storeys. Ugly, with no ‘architecture’. There was a certain identity of the place before that has not been respected.

I’ll give you some examples. Outside the historic centre we used to have single historic buildings, 70 or 80 years old, that used to be build with a garden and red roof tiles. This was the identity of the place. I’m not saying that we shouldn’t change it, but we should not forget about everything that went before. It shouldn’t look like every other new place. There was an identity of the place that you can define in several ways; the identity was multi-layered. You should not just build high rise in each area like every other. There are certain elements of identity; people understand their environment through these things. Now the only difference is the percentage of land built on; you don’t see any difference between any part of town.

AB: I find it hard to imagine how the pattern of development could ‘naturally’ follow the historic grain. Ramallah developed in a certain way for centuries, but then you have this political line that’s drawn on a map in the 1990s that defined only a relatively small area for development, and on top of that the PA decided to base its centre of government here. Surely these impositions make it almost impossible to have a ‘natural’ pattern of development built on what went before?

FM: It’s not only that. In time, things are moving faster than the thinking. We are not thinking about our environment. We are just building. This is the only way we see development; and this is a problem. I don’t know what development is, but I don’t see this as development. It’s getting crazy; people aren’t thinking about spatial issues; how we want our spaces to be. We don’t have a public space in Ramallah. If you go to Manarah [in central Ramallah], one dunam of land (1000sq.m) will cost $4-5million. It’s like that. How can you have a public space?

We are not thinking about our space here, and development has just become about building buildings. Even if we wanted to protect historic buildings there, they would say that it’s sitting on a $1million plot of land and that they’re not ready to protect it. It’s crazy.

AB: It seems like an almost impossible challenge, to educate a mindset that thinks beyond the occupation, when there’s a complete economy that has developed under the constraints of it. I guess that would bring us to a different question. How would you envisage a different situation? And how do you think that the kind of work that you’re doing could offer a way towards that?

FM: Without this influence, how do we want our country to be? We have to think about it. It’s multi-layered. People should discuss their neighbourhoods and how they want them to be. Every place in Ramallah is almost like every other place. There is no public space. There are empty lots that are owned by people, but you can’t use them. We need to think about how we want our country to be in the future rather than to allow these forces to control how we behave. In the end, because of these constraints, the Ministry decided on these zoning policies. But it’s crazy. It’s not like this in other parts of the world. Now it just depends on the landscape; whether you have a slope or not; that’s it. We have a problem. For me it’s not just about the historic centre of Ramallah. It’s also about the areas around the historic centre that have a certain identity that we’re losing.

We should also have plans for the spaces in between; not only these spaces; a national plan for how we want our cities and towns to be. I’m afraid now, because of bypass roads and settlements, there is no natural reserve in Palestine; there is no place to go and just relax; to go and have fun. Wherever you go, you see a bypass road or a building. It’s too much.

AB: Can I go back to the question of this national masterplan? You mentioned the need to not think about the constraints that are there now. Perhaps to think about what is there physically, but not politically. Would you see that there’s any way that even the design of such a masterplan could be realised by organisations outside of the PA?

FM: I think that [the PA] should be involved. In a way they need to be ‘trained’ by this exercise. To tell you the truth, Decolonizing Architecture is about this exercise as well. It’s about imagining what we would do if the Israelis weren’t in these places. I think we need to do these exercises. And this is what we do in the historic centres. That’s why there is a synergy between these two projects. We see the future in these places and we are working on it. They are doing the same; they are talking about the future. It is very important. We don’t dream; we don’t talk about the future so much. I think this is very important. But now I think there are a lot of people, in Ramallah especially, who are starting to talk about these things. They are not that powerful yet, but it’s happening.

For example, in Ramallah there are many committees helping the municipality with how they will deal with issues. Yazid is in one of them; I’m in another one. When you used to go to Manarah, it would be full of signs. It had no identity. They had a suggestion to remove all of these commercial signs, and they chose to remove them. When you go there now, you feel much better. Small things here and there can contribute to making this place better. This is as far as we can go for now.

TE: So you believe more in the kind of discourse that is starting to emerge here?

FM: This is the most interesting thing; and the thing that keeps us in this country. Otherwise I’d leave. I am one of the people that can leave easily. But we believe in what we’re doing. And we think that these things together can contribute and make this a better place. We still have hope… And we go to Italy often to have fun!

TE: Maybe one more question. Would you say that, in a way, Riwaq and Decolonizing Architecture are both looking at the future; about what it would be like without occupation; but the material of heritage that you work with is different? You work with a heritage that dates from before the occupation, whilst Decolonizing Architecture look at the heritage of the occupation.

FM: Yes. You could say that; and this is one of the main differences.

AB: But I suppose another difference is that, in a way, you’re putting facts on the ground. It seems that you’ve also demonstrated the social value of that in how you talked about the local committees and how the interest and involvement increases when you realise projects. Would you see that as a sign that there’s a much bigger potential for what you do than you are able to cater for; that there’s room for other Riwaqs out there to be working everywhere.

FM: This is part of our dream. To have other Riwaqs all over. Really, it’s like hatching eggs; developing another organisation here and there. We cannot do it from here alone. There should be an organisation working on such issues in the north, in the south. It should be that. We can’t do everything. We are trying to set examples and work on a part of our heritage; but you are talking about 10,000 archaeological sites in this small part of the land. Wherever you go; if you dig, you find something.

The most important thing is that people are not aware of this heritage. I’m not saying we’re educating people, but we need to help people to rediscover their potentials again in these places. If they can see the potentials, they will contribute alone. People are educated enough to do things. But people are [also] poor. If you are working for money just to get food for your children, you maybe can’t think about the future. So, we’re trying to say “come, let’s think together”. We can use these places; it costs half the price of building a new building. Let’s try to see how we can use them for your benefit. And it’s working. They get involved when they see it can happen.

AB: All of the projects that you have mentioned realising have basically been within municipal areas. Have you had any projects where you’re coming face to face with the Israeli ‘Civil Administration’ in Area C?

FM: Actually, when we work in Areas B and C we don’t talk to anybody. I’ll give you an example. In the Silwad area, which was on the trail that I talked about, we have the biggest concentration of peasant watchtowers. These are dry stone structures, built a hundred years ago or more, where the peasants used to go out of the village and live in these structures before the cultivation of the crops. They used to watch their crops so that nobody would steal them, and then would bring their crops back to the village. We have a high concentration of these structures in this area, and we are going to work on them with the village council, because it’s a part of the village, even though it’s in Area C. So we are not going to go and get a permit from the Israelis.

AB: So, you’ve never approached them?

FM: They are not there. Khalas (“enough”), we will do whatever we want to do. This is the best way to do it. Even though we applied to the EU for this project and they refused.

AB: Because it was in Area C?

FM: No, not for that reason. Maybe it just didn’t fit their agenda. But we will still try to do it. You get a lot of criticism, even from Palestinians, saying that we are doing it the wrong way. But we did it; nobody else did it. And this is very important.

AB: Otherwise you’re just sitting there talking.

FM: We can’t keep talking. We do things.