Jeff Halper, Director of the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions (ICAHD)

Abridged transcript of interview, recorded in West Jerusalem on Wednesday 9th September 2009

Jeff Halper (JH)

Ahmad Barclay (AB)

Tashy Endres (TE)

TE: We have been talking to different people about spatial agency in the conflict.

AB: We hoped to find ideas about effective routes, and other potentials [for spatial resistance]. I suppose the challenge is, on the Palestinian side, that you have something very fragmented. The problem seems to be that now, even if the Palestinian Authority had ideas that were forward thinking, they don’t have any kind of legitimacy among their own people to push an agenda forward. So, it becomes a much more fragmented question of what spatial planning can be.

TE: I’m very interested in the different understandings of the role of planning, and the role of space and architecture, and the different practices that result from that. I’m very impressed by the work of ICAHD, of course.

AB: I suppose ICAHD are very interesting to us because you, almost uniquely, straddle between direct action and advocacy, and perhaps planning as well?

JH: It’s a very anthropological approach. Anthropologists go from the ground up and then try to look holistically.

TE: And you are an anthropologist by training?

JH: Yes, I’m an anthropologist. I was a professor for many years. I left it to do this work.

I’ve written about this. The whole matrix of control. I’ve written about settlement planning. I’ve written about some of this stuff. But it’s true, more from a political perspective than a theoretical one.

AB: I think there are a lot of publications on the frameworks of control. Especially the Israeli side; for example town planning and how it’s used. But in terms of the role of architects and spatial planners in fighting against that, and working against the occupation, it seems to be a less defined subject area; certainly in terms of framing routes that people can take towards something else. Not just outlining future scenarios, but also the processes in between. Resistance, but a positive form of resistance that also works towards some specific goal.

TE: For our work, it would be good to have a small introduction to what you do.

JH: It’s a political organisation. We’re not a planning organisation. We are a human rights organisation in a way. The whole idea that human rights isn’t something political is bullshit. So, we’re political, and we use all the other tools that are available for ending the occupation; whatever that means. It used to mean a ‘two-state’ idea, but that’s not necessarily the case anymore. But that’s also part of the issue on a bigger level. I’ve been writing a lot about considering the possibility that both the two-state and the one-state idea don’t work, and where would we go from there; writing about a Middle East economic confederation. That also brings in a lot of spatial and economic issues.

AB: I read your piece in one of the PASSIA publications. I found the idea very interesting that you can maybe found a Palestinian state without defining the borders first. The idea that if you don’t start with borders, you outline a slightly different political game.

JH: But this only makes sense in the context of that kind of confederation. What Fayyad is talking about, and what the second phase of the Road Map is talking about, a Palestinian state without borders, isn’t a good thing. If it’s Israel and Palestine, and Palestine has no borders, that’s not a good thing. But the idea of not having borders within an economic confederation, that might work. A little bit like in Europe, where borders become irrelevant in a sense. If you are a Palestinian state that is tiny, borders could become a drawback.

We’re always looking at the spatial issue, connected to issues of sovereignty and self-determination, and economics, and how they would work themselves out. So it’s very much a rounded approach. So, we see ourselves as political activists. We use house demolitions; we use our [rebuilding] projects as a vehicle for a bigger political agenda. We see ourselves as actors, not just as a protest group. We work with governments; we work with the consulates here; we work with the UN and all kinds of organisations to insert ourselves. It’s not easy. Governments don’t like to work with civil society very much, especially on an issue like this. So we have to really push ourselves, but we’ve been very successful for a civil society group.

A lot of our analysis is about putting together the facts on the ground. You have to give people something to hold on to; a description of what’s going on, with a grounded analysis of where it’s all going. Then, from there, offering thoughts forward about where we can go with this whole process. It’s very much a kind of applied planning, I suppose, but in a more political way.

We chose the issue of house demolitions for a few different reasons. First of all it is very visual, so you can show a story of a family. We have films, you can show [political actors] the demolitions. Each demolition is also like a microcosm of the occupation. So it gives you a window into how the occupation works; what Israel’s intentions are, and so on. And then, at the same time, it helps us to ‘reframe’. Politically, what we do we call “reframing the conflict”, because Israel has captured the framing – for the media; for politicians; for the public – and we have to reframe it. So, part of this is that the occupation is not for security; it’s a pro-active policy of claiming the entire country. And then, at another level, the house demolition issue is really the essence of the conflict, because if you deny someone a home on an individual basis – human beings can’t function without homes – it gives a message; and, if you then do it on a collective basis – which Israel has been doing since 1948 – then the message is “get out” as a people.

What we also do is connect up 1948 with what’s happening now, we’re not only occupation-focused. Last year Israel demolished three times more houses inside Israel than it did in the occupied territories. Houses of Arab Citizens of Israel, whether Palestinian or Bedouin. What we’re arguing also is that we need to have a wider pan-Palestine-Israel view not just confined to the occupation. And then we mix our resistance on the ground with advocacy, and we produce maps. I think the maps are very useful, and what we do that nobody else does – even my mapmaker doesn’t like to do it – is that we project. In other words, people who make maps are trained to stay with the facts on the ground; and everything here is the facts on the ground, except the ‘settlement blocks’. This is my analysis, because there is no map of settlement blocks.

[The settlement block issue] is interesting, because the concept of Israel in all of its negotiations is that there are certain settlement blocks that we want to keep; and that’s really the basis of the negotiations, including for the United States. Israel is saying that [former US president] Bush put out this letter in 2004 recognising the settlement blocks, and so if we build within these settlement blocks it’s not violating the Road Map. But there’s no map of the settlement blocks; nobody knows how many there are; the Israeli public has never seen a map; I don’t think the media has ever seen one. Maybe the Ministry of Defence has a map somewhere. So, we put together a map in which we say there are seven settlement blocks. These are like Israel’s bottom line, and then they create the cantons – what [Ariel] Sharon called “cantons” – that are then the basis [of a Palestinian state].

Then we do [another map], which is completely conjectural, of where Israel is going. We call it a Bantustan; we use the Apartheid language. It’s easy to get to this; you take Areas A and B, you take the settlement blocks, you put the line of the wall in, and you come up with this. So, this goes one step further than what most people do with maps because, from my point of view, maps are analytical tools; they’re not just descriptions. And I think that’s very useful for people, because it gives them a way to understand what’s going on. In other words it’s true, the whole spatial planning part of our understanding just flows out of our analysis on the ground.

AB: Do you find that you’re influencing the debate within Israeli society as well as internationally?

JH: No, not at all. We don’t even try anymore. You’re not going to get through to the Israelis. They don’t know the maps. They don’t want to know the maps. The Israelis have been completely neutralised by their leaders; and essentially the way it’s been done is through a simple belief, an assumption, that has been inculcated in Israelis – this is true from before 1948 – that the Arabs are permanent enemies, period. The way that it’s said in public is that you can’t trust the Arabs. So that completely neutralises the Israelis. The Israelis say that we will accept two states, we will do this, we will do that, but we can’t because the Arabs won’t let us. So, in a sense, they’ve disconnected from the occupation; living in a bubble. Life is very good, and the occupation isn’t really a burning issue.

[The occupation] has become, actually, a non-issue in Israel, which means that it’s outside of the political discussion. They’ll get into an argument about religious things, about the economy, about the latest scandal; but the occupation really isn’t that much of an issue. But, at the same time, we feel that the Israeli public will not be an obstacle, because the Israeli public never bought into the settlement enterprise and the occupation. If [US president] Obama came and said the occupation is over, the Israelis would be fine with that. The government would squawk, but most Israelis would be fine with that; I think 70% of the Israeli public.

So we say our job is internationalising; getting to the decision makers abroad; but they’re not going to do anything unless they’re pushed by their own people. So, for example, did you ever hear of the Greenbelt Festival? The Greenbelt is a progressive Christian festival in Cheltenham [UK]. It’s a four day festival which has been running for 30 years now, and it always takes social justice as its theme. You have Christian Aid there; you have all kinds of advocacy groups; groups on hunger in Africa and AIDS; and about 20,000 people come. And the Greenbelt people have take Palestine as their many theme for the next three years. So, I spoke before 10,000 people on the [Cheltenham] racecourse. So that’s happening; churches are starting to kick in; trade unions are starting to kick in. There are a thousand or more organisations – civil society, human rights, political – that are working on it; so it is really becoming the big issue around the world. I was at a demonstration in Korea a couple of months ago, in Seoul, and 50,000 people came for a Palestine event. So, that’s what we do, and that will move things more than here. It’s just not worth trying to work inside Israel.

TE: So outside, internationally, you would just try to speak to anyone?

JH: Really anyone. But we also get [access to politicians]. When I was in Berlin I went to meet this guy Boris, who is the head of the Middle East desk in the Foreign Ministry. A really good guy; his father is a famous journalist; very bright. And then I met in the Bundestag with the committee on human rights; I’ve met the political leaders. We work with Pax Christi; we work with a lot of groups in Germany. In other words we do have really good relations both with the [civil society] groups, but also in governments. We have access to government. I don’t put a lot of hope in the idea that if I’m meeting with them they’re going to change their policy, but that’s a part of it. You engage with them, and at the same time you mobilise the civil society to push them. And it begins to happen.

AB: It’s a very long process?

JH: And the spatial part is crucial. Obviously, if there’s no coherent territorial space for a viable Palestinian state, then we’re talking about something else. We’re talking about one state or something. We use the maps in a very visual way to show people what a settlement block means, and what its intentions are. We have a whole map here on the infrastructure; not many groups deal with the infrastructure. People tend to focus on the occupied territories and Israel [as separate entities]. But it’s one unit [Israel-Palestine].

I’ve written, for example, about the Trans-Israel Highway (Road 6) [that is being built] through the country. It doesn’t come into the occupied territories, so nobody relates to it; but it’s the new demographic spine of Israel. Most of the population lives along the coast, and the idea is to move the population eastwards. This was a whole obstacle before, because it wasn’t populated [by Jews]; it’s rural, it’s poor, it is heavily Arab [in the Galilee and along the Green Line]. It’s a place where Jews didn’t want to move in to. So, between the settlement blocks in the West Bank and the urban centres [on the coast] you had a barrier. By putting a highway through that barrier, all of these things radiate out; you get gas stations; you get restaurants; and then communities, for example Kochav Ya’akov, which is right [on the highway]. Today it is about 6,000 people, and it will be around 150,000 people in the next 10 years.

AB: So it’s right by Qalqilya [in the West Bank].

JH: Just opposite Qalqilya, you see. Nobody would have come in to live there. It was almost a settlement before, but now the highway’s there, and it’s only a few minutes to [downtown Tel Aviv]. This becomes the centre of the country rather than this barren area. That really means that the whole country is being reconfigured; but if you’re only focusing on the West Bank, you don’t see it. And that’s one of the real problems; in terms of the spatial situation, people aren’t relating to the entire country. They’re not seeing that this highway is as crucial to the occupation as a settlement is, because it isn’t in the occupied territories.

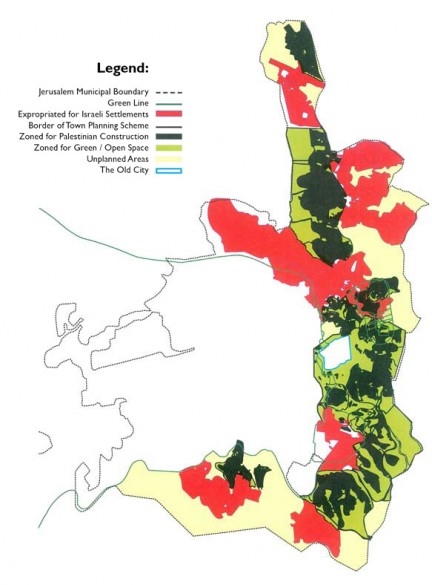

AB: I remember reading a recent UN-OCHA report on Israeli planning policy in East Jerusalem, and the map that they used showed East Jerusalem in isolation, and it was very ambiguous. I would imagine that if you read it with West Jerusalem, you’d see how there are only these national parks and ‘unplanned’ areas in East Jerusalem, and how tiny the built areas are. But on it’s own it didn’t really mean as much. You had to read the explanation.

JH: Then, of course, the question is [also] on borders. Whose East Jerusalem are you talking about? Is this the East Jerusalem that Israel drew the borders of? The Palestinians wouldn’t say that. There’s all those kinds of issues.

What are some of the questions that you’re asking other people?

TE: For me it’s very much on this understanding of space, and also the theoretical approach to space, and how that impacts in spatial practices.

AB: Areas A, B, C in the occupied territories tend to come up as a main point of conversation, even if we’re not asking about them. For example, since it’s so much easier to build in Area A, you get a very strange kind of urbanisation that’s happening in those areas. I suppose the question that we’re asking to a lot of people is about how you can plan Palestinian national infrastructure, and how you can plan national development while this framework exists. Is there even a realm to think about that? To at least project it, or to try to realise something coherent within the framework remains.

TE: It’s interesting for me when you say that the house demolitions work well as a microcosm for the occupation, and that it’s such a strong vehicle to communicate that to an international public. So that’s a different focus to what, for example, Bimkom has. They are acting in legal advocacy, sometimes doing similar things, but their audience is not the international public. It’s very interesting to see space not only as where the conflict takes place, but also as a vehicle for making the conflict transparent.

JH: No, but it’s also a vehicle for imposing a particular political position. That’s the spatial conflict. So, what happens then is you get these things like the Palestinian Authority, which fully accepts the Israeli imposed Areas A, B, C, and that’s where the urban development comes from. That reinforces the idea of their being collaborationists; because they’re basically creating facts on the ground that actually strengthen the Israeli occupation.

Our problem with Bimkom is that our basic principle, or contention, is that in international law Israel has no authority to extend its planning or its legal system in any way into the occupied territories. I think Bimkom undermines human rights, because Bimkom is basically legitimising the Israeli system; because it’s going to the [Jerusalem municipality]. We have to also listen to the Palestinians; it’s their struggle; we have to be the junior partner in this whole thing. So, if the Palestinians say this is occupied territory – which we agree with – and then we go to the municipality to start planning in Jabel Mukaber; what is that? We’re basically undercutting our own position. We’re saying that the [municipality] is legitimate. Or you go to the courts. We don’t do what, say, ACRI does; we don’t go to the Israeli courts.

Sometimes it’s hard, because you’re working with families, and they need your help to get a permit, or they need your help with the court; they have a demolition order. But we say no, we don’t do that. That’s the difference between humanitarian and political work. Bimkom is not political; it’s humanitarian.

AB: I think that’s what they were clear about when we spoke to them. They do whatever works within the current political system; within the laws.

JH: But that’s not good for the Palestinians. In other words you’re helping people in the short term, but how many people can you really help? It’s a skewed system. But, at the same time, you’re in a sense enabling the occupation to function; because you’re getting lawyers, you’re raising money to do masterplans. And it’s the same thing that [PA president] Abu Mazen’s doing. You’re also then planning and building within these parameters. The Israeli system knows what it wants; it knows where it’s expanding; it knows where it wants to control; it knows the spatial stuff better than we do. So the minute you’re cooperating with this; when they approve a plan, it’s not that they’re approving it because we convinced them, or we pressured them. It’s because the parameters that they approved are parameters that they can live with. So in the end, if you think that they’re your partners somehow; they’re not; and that’s where we depart from Bimkom. The whole point of us is to resist the occupation.

TE: So you do not apply, for example, for construction permits when you rebuild?

JH: No. We don’t do that. We don’t go to court. Occasionally we’ve gone to court with a family that we’ve rebuilt for that’s got into trouble. We do have a certain responsibility to families we work with; but that’s a minority thing, and it’s not at all a part of our work. We keep the focus on the political. We’re against mixing political and humanitarian work. Especially as Israelis, we have no right; we’re not the social workers of the Palestinians.

AB: From a Palestinian perspective, the initial conversations we had were about planning within Areas A, B, C. How can you realise parts of you masterplan and perhaps work with the Israeli authorities to realise the rest of it? And then we had a discussion with Riwaq, who were talking about creating regional networks between villages, and they said they had no intention to work with the Israeli authorities.

JH: They don’t apply to the authorities?

AB: They’re not doing [these projects] in a big way yet, but that might be the next stage. This approach was a kind of breath of fresh air after our other conversations. In our other conversations we spoke about the question of ‘future’ planning. Planning for some kind of space that could be viable within a one-state or a two-state solution. In Area A now they’re creating these spaces that aren’t really viable, and threatening to the cultural heritage that they have there. So up to then I had been wondering whether you could work within the existing framework to plan for national infrastructure. [Riwaq’s] position, and your own position, seems to be about going ahead and building it [rather than simply planning].

JH: When we build, we don’t ask for permits. It’s civil disobedience. The whole point we’re making is that we’re building in conformity with international law, because people have rights to housing. But it’s in violation of Israeli law, because it’s Israeli law that says they need permits. It would be ridiculous for us to go and get a building permit for people, and then say that we’re resisting anything.

AB: With the situation that you spoke about of three times more demolitions occuring within Israel than the occupied territories, are you advocating there as well? Because there it would presumably be more problematic since, within Israeli territory, Israeli law is internationally recognised and obviously has more validity, even if it is used for the same purposes as in the occupied territories.

JH: It does. There you can go to courts; and there you can do things. We don’t push it that way. We do keep our focus on the occupation. There are other organisations that are dealing with that in Israel, but at the same time it’s very interesting because neither the Bedouins nor the Palestinian Citizens of Israel want to be lumped in with the Palestinians of the West Bank. So, when we come and say that we’re looking from a 1948 perspective; that this is still ethnic cleansing; they’re still being driven off the land, they don’t like that. They know they’re living in Israel; they’re Israeli citizens; that’s their reality. So their struggle is to convince [Jewish] Israelis that they’re really loyal Israeli citizens.

In a sense they would see it as counter-productive to their wider interests inside Israel if people began to perceive them like they perceive Palestinians in the West Bank. That would reinforce the idea that they’re a ‘fifth column’; they’re the enemies; they’re not really Israelis. So, it’s not easy, and we don’t really push them very much on that. So we come, and we do some rebuilding, but it’s on a much lower flame. It’s more couched in terms of Bedouin rights. And then we’ve even worked with Jews. There was a poor working class Jewish neighbourhood in Tel Aviv called Kfar Shalem – it was actually built on top of a Palestinian village – of Yemenite immigrants that was also displaced last year. We came in to work with them as well, because it’s a form of economic displacement, but it’s still displacement. So we’ve done that, but we’re really trying to keep the focus on the occupation.

TE: Where do you get your resources, your funding from?

JH: Partly we’re on the ground. That’s where you understand what’s going on. But actually we’re not a research group; we don’t have the resources for that, and there’s no point in replicating what other groups are doing. B’Tselem has information on house demolition figures, even the municipality will give information on that. There’s a million groups that have data; OCHA, Amnesty, Human Rights Watch. We let them do the research and we take their data and we integrate it into our analysis. We’re there, so we have a grounded analysis – we know enough – then we use their figures to make our case stronger. Normally the data doesn’t change our analysis; it reinforces it.

AB: In terms of funding for the actual rebuilding of houses; is that all private donations, or are you able to get anything through governments?

JH: We just did this work camp in Anata that was paid for by the Spanish government. It’s the second year. They even paid for forty young Spanish people to fly over to be volunteers. We get support from certain church groups, Christian Aid in the UK, Appo Vev in Europe, the Church of Sweden built a whole house once, an American Christian group built a house. We get that, but it’s mainly private donations. I go out and I pass the hat; and we have what are called the ‘house parties’. We have a whole packet with a film and CDs and materials, and then people invite 10 or 15 neighbours or colleagues. You invite them in, and they have an evening where they learn about this issue, and then people donate money.

AB: In terms of measuring the success or failure of what ICAHD is doing; what would you see as your barometer?

JH: Our barometer is to what degree we have mobilised the international public. Now, it’s not us alone obviously, but we’ve played a major role in that. We’re the only Israeli group that systematically engages in international advocacy. Most Israeli groups just do local actions. You know Ta’ayush and Anarchists [Against the Wall]. They do good stuff, but it’s all local. Nobody goes out. I don’t think any Israeli group has ever heard of Greenbelt or the Muslim community of Sheffield. The fact that we get to these places means that not only are we known, but we’re accessible, we’re user friendly. You can invite us and we’ll come. You could invite, say, Uri Avnery to come; he’s not going to go to Sheffield. He’ll go to London for something. Or Hanan Ashrawi for that matter; the Palestinians as well. So [Avnery] will come and he’ll give a talk at a conference, and then he’ll go home. In other words they don’t spend the time networking. When I’m in a city I’m giving talks; I’m meeting activists; I’m meeting political people; I’m meeting the media; I’m strategising with groups and sharing our materials. I’m a resource person; and I think that plays a role in this; we literally work with hundreds of groups. So, that’s my barometer. Not the governments; because governments will fall into place last. You’ve got to build this critical mass.

Take the BDS movement for example. We were part of the beginning of the BDS movement; we were the first Israeli organisation to endorse it when it was just about Caterpillar. Then they got into other things; and now it has its own life; nobody controls it. You’ve got things all over. I’m going to Italy now in Genoa, and I’m going to be at a press conference about Agrexco. No-one from here initiated a campaign against Agrexco; that was the Italians; they opened their eyes and they saw. In Britain now there’s a lot of stuff on arms starting to develop. It doesn’t need pushing from here anymore. People have the materials; and they get it, and then it starts to spread like wildfire. I think that’s what’s happening, and that’s our barometer; because that’s not going to go away. That’s going to grow more and more all the time. It doesn’t matter what government we have. But our role then is to plug in this analysis, because they’re activists, but they don’t have time to go research this stuff, so we’re always feeding our materials to them so they have something to work with. Again, the spatial stuff is crucial.

TE: So you see that decentralised grassroots thing as a strength rather than a problem?

JH: Well, it’s both. You couldn’t run that kind of a campaign too centralised. On the other hand, you could have a little more coordination. It’s tiring to be the only group going out. Now I’m doing ten cities in Italy in two weeks. Then I come back for two days and I’m going back to Britain. I’m speaking at the Labour Party convention in Brighton. I spoke for the Liberal Democrats last year. I spoke with the Conservative Friends of the Middle East on this last trip. I’m speaking with the Labour Party, and then I go to the States for a month. I do a lot of work in Washington.

It would be good if there was more of a Palestinian presence, but it’s very hit and miss, and coordination isn’t very good. This whole normalisation thing, which I understand, in a way, really hurts the Palestinians. They’re cutting themselves off from really important sources of support; but that’s their decision. But I’m going there now. I’m going to Ramallah in a few minutes to meet with the NSU (Negotiations Support Unit), which is part of the PLO involved in negotiations. So, we’re trying to help them to reframe their position. So we’re working with Palestinians; even the PA.

AB: What situation would you like to see on that side in terms of communication? What do you think would be the most positive change in the current situation that could facilitate something that’s more cohesive?

JH: Well, the key concept here is ‘viability’, which is a word that’s in the Road Map. In other words there has to be a viable entity; if there’s a Palestinian state in a two-state solution it’s got to be viable. If it’s a one-state solution there’s got to be a viability in some expression of sovereignty or self-determination for Palestinians. So that, I think, is the issue; and if it’s not one-state, what is it about? What’s a viable solution?

What we’ve done is we’ve identified six elements that have to be a part of any solution. In other words, instead of advocating for any particular solution, which we say is the Palestinians’ prerogative; it’s not our right to do that. Instead, we say there are six elements that have to be present in any solution, including self-determination and economic viability. It makes it more concrete; if you have a two-state solution, can you have viability and sovereignty and self-determination with settlement blocks? Can you have those for a regional confederation? Well; how do self-determination and economic viability fit into that? Economic viability and self-determination; those are the things that are going to guide you in terms of which spatial solution to have.

You can’t do a spatial solution without knowing what you are trying to capture. That’s the problem, because Israel has got people to think about this in spatial terms and not political terms. So, Israel says they’ll give the Palestinians 90% of the occupied territories, and people say “woah, that’s pretty good.” But it begs the question “what’s the other 10%?” or even with 5%, which is a spatial-political question. They could get 95% of the territory – maybe 99% of the territory – and with that 1% or 5% Israel can still make it a Bantustan by doing certain things. The analogy we use is a prison, which this is. We say to imagine you are looking at the blueprint of a prison. Now, if you look at the plan, it looks like prisoners own the place. They have 95% of the space; they have the living areas, they have the cafeteria, they have the work areas, they have the exercise yard. And all the security guards have [is the other 5%]; if it’s a minimal security prison, all they have is 1%; that’s it. You’ve got a few corridors; you’ve got a couple of locked doors, and that’s it; that’s all you need. So the issue is control; it’s not [only] territory.

Interview Transcript #5

Interview with Jeff Halper of the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions (ICAHD)

West Jerusalem, Israel

1:00pm, Wednesday 9th September 2009

Jeff Halper (JH)

Ahmad Barclay (AB)

Tashy Endres (TE)

TE: We have been talking to different people about spatial agency in the conflict.

AB: We hoped to find ideas about effective routes, and other potentials [for spatial resistance]. I suppose the challenge is, on the Palestinian side, that you have something very fragmented. The problem seems to be that now, even if the Palestinian Authority had ideas that were forward thinking, they don’t have any kind of legitimacy among their own people to push an agenda forward. So, it becomes a much more fragmented question of what spatial planning can be.

TE: I’m very interested in the different understandings of the role of planning, and the role of space and architecture, and the different practices that result from that. I’m very impressed by the work of ICAHD, of course.

AB: I suppose ICAHD are very interesting to us because you, almost uniquely, straddle between direct action and advocacy, and perhaps planning as well?

JH: It’s a very anthropological approach. Anthropologists go from the ground up and then try to look holistically.

TE: And you are an anthropologist by training?

JH: Yes, I’m an anthropologist. I was a professor for many years. I left it to do this work.

I’ve written about this. The whole matrix of control. I’ve written about settlement planning. I’ve written about some of this stuff. But it’s true, more from a political perspective than a theoretical one.

AB: I think there are a lot of publications on the frameworks of control. Especially the Israeli side; for example town planning and how it’s used. But in terms of the role of architects and spatial planners in fighting against that, and working against the occupation, it seems to be a less defined subject area; certainly in terms of framing routes that people can take towards something else. Not just outlining future scenarios, but also the processes in between. Resistance, but a positive form of resistance that also works towards some specific goal.

TE: For our work, it would be good to have a small introduction to what you do.

JH: It’s a political organisation. We’re not a planning organisation. We are a human rights organisation in a way. The whole idea that human rights isn’t something political is bullshit. So, we’re political, and we use all the other tools that are available for ending the occupation; whatever that means. It used to mean a ‘two-state’ idea, but that’s not necessarily the case anymore. But that’s also part of the issue on a bigger level. I’ve been writing a lot about considering the possibility that both the two-state and the one-state idea don’t work, and where would we go from there; writing about a Middle East economic confederation. That also brings in a lot of spatial and economic issues.

AB: I read your piece in one of the PASSIA publications. I found the idea very interesting that you can maybe found a Palestinian state without defining the borders first. The idea that if you don’t start with borders, you outline a slightly different political game.

JH: But this only makes sense in the context of that kind of confederation. What Fayyad is talking about, and what the second phase of the Road Map is talking about, a Palestinian state without borders, isn’t a good thing. If it’s Israel and Palestine, and Palestine has no borders, that’s not a good thing. But the idea of not having borders within an economic confederation, that might work. A little bit like in Europe, where borders become irrelevant in a sense. If you are a Palestinian state that is tiny, borders could become a drawback.

We’re always looking at the spatial issue, connected to issues of sovereignty and self-determination, and economics, and how they would work themselves out. So it’s very much a rounded approach. So, we see ourselves as political activists. We use house demolitions; we use our [rebuilding] projects as a vehicle for a bigger political agenda. We see ourselves as actors, not just as a protest group. We work with governments; we work with the consulates here; we work with the UN and all kinds of organisations to insert ourselves. It’s not easy. Governments don’t like to work with civil society very much, especially on an issue like this. So we have to really push ourselves, but we’ve been very successful for a civil society group.

A lot of our analysis is about putting together the facts on the ground. You have to give people something to hold on to; a description of what’s going on, with a grounded analysis of where it’s all going. Then, from there, offering thoughts forward about where we can go with this whole process. It’s very much a kind of applied planning, I suppose, but in a more political way.

We chose the issue of house demolitions for a few different reasons. First of all it is very visual, so you can show a story of a family. We have films, you can show [political actors] the demolitions. Each demolition is also like a microcosm of the occupation. So it gives you a window into how the occupation works; what Israel’s intentions are, and so on. And then, at the same time, it helps us to ‘reframe’. Politically, what we do we call “reframing the conflict”, because Israel has captured the framing – for the media; for politicians; for the public – and we have to reframe it. So, part of this is that the occupation is not for security; it’s a pro-active policy of claiming the entire country. And then, at another level, the house demolition issue is really the essence of the conflict, because if you deny someone a home on an individual basis – human beings can’t function without homes – it gives a message; and, if you then do it on a collective basis – which Israel has been doing since 1948 – then the message is “get out” as a people.

What we also do is connect up 1948 with what’s happening now, we’re not only occupation-focused. Last year Israel demolished three times more houses inside Israel than it did in the occupied territories. Houses of Arab Citizens of Israel, whether Palestinian or Bedouin. What we’re arguing also is that we need to have a wider pan-Palestine-Israel view not just confined to the occupation. And then we mix our resistance on the ground with advocacy, and we produce maps. I think the maps are very useful, and what we do that nobody else does – even my mapmaker doesn’t like to do it – is that we project. In other words, people who make maps are trained to stay with the facts on the ground; and everything here is the facts on the ground, except the ‘settlement blocks’. This is my analysis, because there is no map of settlement blocks.

[The settlement block issue] is interesting, because the concept of Israel in all of its negotiations is that there are certain settlement blocks that we want to keep; and that’s really the basis of the negotiations, including for the United States. Israel is saying that [former US president] Bush put out this letter in 2004 recognising the settlement blocks, and so if we build within these settlement blocks it’s not violating the Road Map. But there’s no map of the settlement blocks; nobody knows how many there are; the Israeli public has never seen a map; I don’t think the media has ever seen one. Maybe the Ministry of Defence has a map somewhere. So, we put together a map in which we say there are seven settlement blocks. These are like Israel’s bottom line, and then they create the cantons – what [Ariel] Sharon called “cantons” – that are then the basis [of a Palestinian state].

Then we do [another map], which is completely conjectural, of where Israel is going. We call it a Bantustan; we use the Apartheid language. It’s easy to get to this; you take Areas A and B, you take the settlement blocks, you put the line of the wall in, and you come up with this. So, this goes one step further than what most people do with maps because, from my point of view, maps are analytical tools; they’re not just descriptions. And I think that’s very useful for people, because it gives them a way to understand what’s going on. In other words it’s true, the whole spatial planning part of our understanding just flows out of our analysis on the ground.

AB: Do you find that you’re influencing the debate within Israeli society as well as internationally?

JH: No, not at all. We don’t even try anymore. You’re not going to get through to the Israelis. They don’t know the maps. They don’t want to know the maps. The Israelis have been completely neutralised by their leaders; and essentially the way it’s been done is through a simple belief, an assumption, that has been inculcated in Israelis – this is true from before 1948 – that the Arabs are permanent enemies, period. The way that it’s said in public is that you can’t trust the Arabs. So that completely neutralises the Israelis. The Israelis say that we will accept two states, we will do this, we will do that, but we can’t because the Arabs won’t let us. So, in a sense, they’ve disconnected from the occupation; living in a bubble. Life is very good, and the occupation isn’t really a burning issue.

[The occupation] has become, actually, a non-issue in Israel, which means that it’s outside of the political discussion. They’ll get into an argument about religious things, about the economy, about the latest scandal; but the occupation really isn’t that much of an issue. But, at the same time, we feel that the Israeli public will not be an obstacle, because the Israeli public never bought into the settlement enterprise and the occupation. If [US president] Obama came and said the occupation is over, the Israelis would be fine with that. The government would squawk, but most Israelis would be fine with that; I think 70% of the Israeli public.

So we say our job is internationalising; getting to the decision makers abroad; but they’re not going to do anything unless they’re pushed by their own people. So, for example, did you ever hear of the Greenbelt Festival? The Greenbelt is a progressive Christian festival in Cheltenham [UK]. It’s a four day festival which has been running for 30 years now, and it always takes social justice as its theme. You have Christian Aid there; you have all kinds of advocacy groups; groups on hunger in Africa and AIDS; and about 20,000 people come. And the Greenbelt people have take Palestine as their many theme for the next three years. So, I spoke before 10,000 people on the [Cheltenham] racecourse. So that’s happening; churches are starting to kick in; trade unions are starting to kick in. There are a thousand or more organisations – civil society, human rights, political – that are working on it; so it is really becoming the big issue around the world. I was at a demonstration in Korea a couple of months ago, in Seoul, and 50,000 people came for a Palestine event. So, that’s what we do, and that will move things more than here. It’s just not worth trying to work inside Israel.

TE: So outside, internationally, you would just try to speak to anyone?

JH: Really anyone. But we also get [access to politicians]. When I was in Berlin I went to meet this guy Boris, who is the head of the Middle East desk in the Foreign Ministry. A really good guy; his father is a famous journalist; very bright. And then I met in the Bundestag with the committee on human rights; I’ve met the political leaders. We work with Pax Christi; we work with a lot of groups in Germany. In other words we do have really good relations both with the [civil society] groups, but also in governments. We have access to government. I don’t put a lot of hope in the idea that if I’m meeting with them they’re going to change their policy, but that’s a part of it. You engage with them, and at the same time you mobilise the civil society to push them. And it begins to happen.

AB: It’s a very long process?

JH: And the spatial part is crucial. Obviously, if there’s no coherent territorial space for a viable Palestinian state, then we’re talking about something else. We’re talking about one state or something. We use the maps in a very visual way to show people what a settlement block means, and what its intentions are. We have a whole map here on the infrastructure; not many groups deal with the infrastructure. People tend to focus on the occupied territories and Israel [as separate entities]. But it’s one unit [Israel-Palestine].

I’ve written, for example, about the Trans-Israel Highway (Road 6) [that is being built] through the country. It doesn’t come into the occupied territories, so nobody relates to it; but it’s the new demographic spine of Israel. Most of the population lives along the coast, and the idea is to move the population eastwards. This was a whole obstacle before, because it wasn’t populated [by Jews]; it’s rural, it’s poor, it is heavily Arab [in the Galilee and along the Green Line]. It’s a place where Jews didn’t want to move in to. So, between the settlement blocks in the West Bank and the urban centres [on the coast] you had a barrier. By putting a highway through that barrier, all of these things radiate out; you get gas stations; you get restaurants; and then communities, for example Kochav Ya’akov, which is right [on the highway]. Today it is about 6,000 people, and it will be around 150,000 people in the next 10 years.

AB: So it’s right by Qalqilya [in the West Bank].

JH: Just opposite Qalqilya, you see. Nobody would have come in to live there. It was almost a settlement before, but now the highway’s there, and it’s only a few minutes to [downtown Tel Aviv]. This becomes the centre of the country rather than this barren area. That really means that the whole country is being reconfigured; but if you’re only focusing on the West Bank, you don’t see it. And that’s one of the real problems; in terms of the spatial situation, people aren’t relating to the entire country. They’re not seeing that this highway is as crucial to the occupation as a settlement is, because it isn’t in the occupied territories.

AB: I remember reading a recent OCHA report on Israeli planning policy in East Jerusalem, and the map that they used showed East Jerusalem in isolation, and it was very ambiguous. I would imagine that if you read it with West Jerusalem, you’d see how there are only these national parks and ‘unplanned’ areas in East Jerusalem, and how tiny the built areas are. But on it’s own it didn’t really mean as much. You had to read the explanation.

JH: Then, of course, the question is [also] on borders. Whose East Jerusalem are you talking about? Is this the East Jerusalem that Israel drew the borders of? The Palestinians wouldn’t say that. There’s all those kinds of issues.

What are some of the questions that you’re asking other people?

TE: For me it’s very much on this understanding of space, and also the theoretical approach to space, and how that impacts in spatial practices.

AB: Areas A, B, C in the occupied territories tend to come up as a main point of conversation, even if we’re not asking about them. For example, since it’s so much easier to build in Area A, you get a very strange kind of urbanisation that’s happening in those areas. I suppose the question that we’re asking to a lot of people is about how you can plan Palestinian national infrastructure, and how you can plan national development while this framework exists. Is there even a realm to think about that? To at least project it, or to try to realise something coherent within the framework remains.

TE: It’s interesting for me when you say that the house demolitions work well as a microcosm for the occupation, and that it’s such a strong vehicle to communicate that to an international public. So that’s a different focus to what, for example, Bimkom has. They are acting in legal advocacy, sometimes doing similar things, but their audience is not the international public. It’s very interesting to see space not only as where the conflict takes place, but also as a vehicle for making the conflict transparent.

JH: No, but it’s also a vehicle for imposing a particular political position. That’s the spatial conflict. So, what happens then is you get these things like the Palestinian Authority, which fully accepts the Israeli imposed Areas A, B, C, and that’s where the urban development comes from. That reinforces the idea of their being collaborationists; because they’re basically creating facts on the ground that actually strengthen the Israeli occupation.

Our problem with Bimkom is that our basic principle, or contention, is that in international law Israel has no authority to extend its planning or its legal system in any way into the occupied territories. I think Bimkom undermines human rights, because Bimkom is basically legitimising the Israeli system; because it’s going to the [Jerusalem municipality]. We have to also listen to the Palestinians; it’s their struggle; we have to be the junior partner in this whole thing. So, if the Palestinians say this is occupied territory – which we agree with – and then we go to the municipality to start planning in Jabel Mukaber; what is that? We’re basically undercutting our own position. We’re saying that the [municipality] is legitimate. Or you go to the courts. We don’t do what, say, ACRI does; we don’t go to the Israeli courts.

Sometimes it’s hard, because you’re working with families, and they need your help to get a permit, or they need your help with the court; they have a demolition order. But we say no, we don’t do that. That’s the difference between humanitarian and political work. Bimkom is not political; it’s humanitarian.

AB: I think that’s what they were clear about when we spoke to them. They do whatever works within the current political system; within the laws.

JH: But that’s not good for the Palestinians. In other words you’re helping people in the short term, but how many people can you really help? It’s a skewed system. But, at the same time, you’re in a sense enabling the occupation to function; because you’re getting lawyers, you’re raising money to do masterplans. And it’s the same thing that [PA president] Abu Mazen’s doing. You’re also then planning and building within these parameters. The Israeli system knows what it wants; it knows where it’s expanding; it knows where it wants to control; it knows the spatial stuff better than we do. So the minute you’re cooperating with this; when they approve a plan, it’s not that they’re approving it because we convinced them, or we pressured them. It’s because the parameters that they approved are parameters that they can live with. So in the end, if you think that they’re your partners somehow; they’re not; and that’s where we depart from Bimkom. The whole point of us is to resist the occupation.

TE: So you do not apply, for example, for construction permits when you rebuild?

JH: No. We don’t do that. We don’t go to court. Occasionally we’ve gone to court with a family that we’ve rebuilt for that’s got into trouble. We do have a certain responsibility to families we work with; but that’s a minority thing, and it’s not at all a part of our work. We keep the focus on the political. We’re against mixing political and humanitarian work. Especially as Israelis, we have no right; we’re not the social workers of the Palestinians.

AB: From a Palestinian perspective, the initial conversations we had were about planning within Areas A, B, C. How can you realise parts of you masterplan and perhaps work with the Israeli authorities to realise the rest of it? And then we had a discussion with Riwaq, who were talking about creating regional networks between villages, and they said they had no intention to work with the Israeli authorities.

JH: They don’t apply to the authorities?

AB: They’re not doing [these projects] in a big way yet, but that might be the next stage. This approach was a kind of breath of fresh air after our other conversations. In our other conversations we spoke about the question of ‘future’ planning. Planning for some kind of space that could be viable within a one-state or a two-state solution. In Area A now they’re creating these spaces that aren’t really viable, and threatening to the cultural heritage that they have there. So up to then I had been wondering whether you could work within the existing framework to plan for national infrastructure. [Riwaq’s] position, and your own position, seems to be about going ahead and building it [rather than simply planning].

JH: When we build, we don’t ask for permits. It’s civil disobedience. The whole point we’re making is that we’re building in conformity with international law, because people have rights to housing. But it’s in violation of Israeli law, because it’s Israeli law that says they need permits. It would be ridiculous for us to go and get a building permit for people, and then say that we’re resisting anything.

AB: With the situation that you spoke about of three times more demolitions occuring within Israel than the occupied territories, are you advocating there as well? Because there it would presumably be more problematic since, within Israeli territory, Israeli law is internationally recognised and obviously has more validity, even if it is used for the same purposes as in the occupied territories.

JH: It does. There you can go to courts; and there you can do things. We don’t push it that way. We do keep our focus on the occupation. There are other organisations that are dealing with that in Israel, but at the same time it’s very interesting because neither the Bedouins nor the Palestinian Citizens of Israel want to be lumped in with the Palestinians of the West Bank. So, when we come and say that we’re looking from a 1948 perspective; that this is still ethnic cleansing; they’re still being driven off the land, they don’t like that. They know they’re living in Israel; they’re Israeli citizens; that’s their reality. So their struggle is to convince [Jewish] Israelis that they’re really loyal Israeli citizens.

In a sense they would see it as counter-productive to their wider interests inside Israel if people began to perceive them like they perceive Palestinians in the West Bank. That would reinforce the idea that they’re a ‘fifth column’; they’re the enemies; they’re not really Israelis. So, it’s not easy, and we don’t really push them very much on that. So we come, and we do some rebuilding, but it’s on a much lower flame. It’s more couched in terms of Bedouin rights. And then we’ve even worked with Jews. There was a poor working class Jewish neighbourhood in Tel Aviv called Kfar Shalem – it was actually built on top of a Palestinian village – of Yemenite immigrants that was also displaced last year. We came in to work with them as well, because it’s a form of economic displacement, but it’s still displacement. So we’ve done that, but we’re really trying to keep the focus on the occupation.

TE: Where do you get your resources, your funding from?

JH: Partly we’re on the ground. That’s where you understand what’s going on. But actually we’re not a research group; we don’t have the resources for that, and there’s no point in replicating what other groups are doing. B’Tselem has information on house demolition figures, even the municipality will give information on that. There’s a million groups that have data; OCHA, Amnesty, Human Rights Watch. We let them do the research and we take their data and we integrate it into our analysis. We’re there, so we have a grounded analysis – we know enough – then we use their figures to make our case stronger. Normally the data doesn’t change our analysis; it reinforces it.

AB: In terms of funding for the actual rebuilding of houses; is that all private donations, or are you able to get anything through governments?

JH: We just did this work camp in Anata that was paid for by the Spanish government. It’s the second year. They even paid for forty young Spanish people to fly over to be volunteers. We get support from certain church groups, Christian Aid in the UK, Appo Vev in Europe, the Church of Sweden built a whole house once, an American Christian group built a house. We get that, but it’s mainly private donations. I go out and I pass the hat; and we have what are called the ‘house parties’. We have a whole packet with a film and CDs and materials, and then people invite 10 or 15 neighbours or colleagues. You invite them in, and they have an evening where they learn about this issue, and then people donate money.

AB: In terms of measuring the success or failure of what ICAHD is doing; what would you see as your barometer?

JH: Our barometer is to what degree we have mobilised the international public. Now, it’s not us alone obviously, but we’ve played a major role in that. We’re the only Israeli group that systematically engages in international advocacy. Most Israeli groups just do local actions. You know Ta’ayush and Anarchists [Against the Wall]. They do good stuff, but it’s all local. Nobody goes out. I don’t think any Israeli group has ever heard of Greenbelt or the Muslim community of Sheffield. The fact that we get to these places means that not only are we known, but we’re accessible, we’re user friendly. You can invite us and we’ll come. You could invite, say, Uri Avnery to come; he’s not going to go to Sheffield. He’ll go to London for something. Or Hanan Ashrawi for that matter; the Palestinians as well. So [Avnery] will come and he’ll give a talk at a conference, and then he’ll go home. In other words they don’t spend the time networking. When I’m in a city I’m giving talks; I’m meeting activists; I’m meeting political people; I’m meeting the media; I’m strategising with groups and sharing our materials. I’m a resource person; and I think that plays a role in this; we literally work with hundreds of groups. So, that’s my barometer. Not the governments; because governments will fall into place last. You’ve got to build this critical mass.

Take the BDS movement for example. We were part of the beginning of the BDS movement; we were the first Israeli organisation to endorse it when it was just about Caterpillar. Then they got into other things; and now it has its own life; nobody controls it. You’ve got things all over. I’m going to Italy now in Genoa, and I’m going to be at a press conference about Agrexco. No-one from here initiated a campaign against Agrexco; that was the Italians; they opened their eyes and they saw. In Britain now there’s a lot of stuff on arms starting to develop. It doesn’t need pushing from here anymore. People have the materials; and they get it, and then it starts to spread like wildfire. I think that’s what’s happening, and that’s our barometer; because that’s not going to go away. That’s going to grow more and more all the time. It doesn’t matter what government we have. But our role then is to plug in this analysis, because they’re activists, but they don’t have time to go research this stuff, so we’re always feeding our materials to them so they have something to work with. Again, the spatial stuff is crucial.

TE: So you see that decentralised grassroots thing as a strength rather than a problem?

JH: Well, it’s both. You couldn’t run that kind of a campaign too centralised. On the other hand, you could have a little more coordination. It’s tiring to be the only group going out. Now I’m doing ten cities in Italy in two weeks. Then I come back for two days and I’m going back to Britain. I’m speaking at the Labour Party convention in Brighton. I spoke for the Liberal Democrats last year. I spoke with the Conservative Friends of the Middle East on this last trip. I’m speaking with the Labour Party, and then I go to the States for a month. I do a lot of work in Washington.

It would be good if there was more of a Palestinian presence, but it’s very hit and miss, and coordination isn’t very good. This whole normalisation thing, which I understand, in a way, really hurts the Palestinians. They’re cutting themselves off from really important sources of support; but that’s their decision. But I’m going there now. I’m going to Ramallah in a few minutes to meet with the NSU (Negotiations Support Unit), which is part of the PLO involved in negotiations. So, we’re trying to help them to reframe their position. So we’re working with Palestinians; even the PA.

AB: What situation would you like to see on that side in terms of communication? What do you think would be the most positive change in the current situation that could facilitate something that’s more cohesive?

JH: Well, the key concept here is ‘viability’, which is a word that’s in the Road Map. In other words there has to be a viable entity; if there’s a Palestinian state in a two-state solution it’s got to be viable. If it’s a one-state solution there’s got to be a viability in some expression of sovereignty or self-determination for Palestinians. So that, I think, is the issue; and if it’s not one-state, what is it about? What’s a viable solution?

What we’ve done is we’ve identified six elements that have to be a part of any solution. In other words, instead of advocating for any particular solution, which we say is the Palestinians’ prerogative; it’s not our right to do that. Instead, we say there are six elements that have to be present in any solution, including self-determination and economic viability. It makes it more concrete; if you have a two-state solution, can you have viability and sovereignty and self-determination with settlement blocks? Can you have those for a regional confederation? Well; how do self-determination and economic viability fit into that? Economic viability and self-determination; those are the things that are going to guide you in terms of which spatial solution to have.

You can’t do a spatial solution without knowing what you are trying to capture. That’s the problem, because Israel has got people to think about this in spatial terms and not political terms. So, Israel says they’ll give the Palestinians 90% of the occupied territories, and people say “woah, that’s pretty good.” But it begs the question “what’s the other 10%?” or even with 5%, which is a spatial-political question. They could get 95% of the territory – maybe 99% of the territory – and with that 1% or 5% Israel can still make it a Bantustan by doing certain things. The analogy we use is a prison, which this is. We say to imagine you are looking at the blueprint of a prison. Now, if you look at the plan, it looks like prisoners own the place. They have 95% of the space; they have the living areas, they have the cafeteria, they have the work areas, they have the exercise yard. And all the security guards have [is the other 5%]; if it’s a minimal security prison, all they have is 1%; that’s it. You’ve got a few corridors; you’ve got a couple of locked doors, and that’s it; that’s all you need. So the issue is control; it’s not [only] territory.