Denis Wood, independent scholar and author of Rethinking the Power of Maps

(full bio below interview).

The following is a written exchange which took place in July 2011.

Denis Wood (DW)

Linda Quiquivix (LQ)

LQ: You argue that maps “as we know them” are only 500-600 years old at most. How do you define maps as we know them?

DW: Because maps are so ubiquitous in our lives today and because we use them to help us do so many things, people find it hard to imagine life without maps. But people didn’t used to have cars either, or cell phones, and we can – with effort – imagine a world without those. Maybe it’s because maps have such a strong “cognitive dimension” that they seem less, I don’t know, technologies than extensions of our mind. But maps are a material technology and a comparatively novel one.

Anyhow what I mean by “maps as we know them” is … maps as we know them: the things you reach for when someone asks you to hand them that map on the table, the things you call maps when you see them in newspapers and magazines, the things you consult online. When you ask for a map you don’t expect someone to dance or sing you a song or hand you a bunch of sticks lashed together with strings or a carved piece of wood shaped something like a bone. When things like these contain locative references some historians of mapmaking want to say that they’re maps. They’re not. They’re something else, no less valuable or interesting than maps, but not maps.

Maybe an analogy would help. Historians of computers like to point to early computer-like devices such as the Jacquard loom which was controlled by punched cards, or to Charles Babbage’s difference and analytical engines, or even to the rooms full of people called “computers” who performed calculations during the 19th and 20th centuries up through World War II. Some even dredge up the abacus. Now they may all have been “computers” in some very general sense – anything that computes could be a called a computer: you, me – but they’re not computers as we know them, not anything like computers as we know them which are electronic devices that date to no earlier than the mid-20th century.

It’s the same with maps. Just because we can find our way around doesn’t mean we’re a map or that we have maps in our heads. Maps as we know them – common, widespread, until recently most often on paper – date to not much earlier than the 15th century (probably the 12th in China). Like most technology they respond to the need that called them into being. As the Jacquard loom was called into being by the industrialization of weaving, so the map was called into being by the early modern state.

LQ: What was it about the rise of the state that needed the map?

DW: The modern state needed the map to do things that overlapped and fed into each other in rich, complicated ways, so this history is not simple. Certainly the state would come increasingly to rely on maps to make legible its appropriation landscape, that is, where land, labor, grain, and other resources could be found and appropriated: seized, taxed, conscripted, put to work. But there had been other ways of doing this – censuses for example – so while advantageous, the map had no unique advantage there. What the map alone could do was visualize borders. We can think about borders as an innovation of the modern state. Traditional states rarely had what we think about as borders. What they had were frontiers: zones of diminishing, ambiguous, often mixed control. The modern state was territorial in a new way and the map was uniquely capacitated to visualize it, to, in the wonderful phrase of Thongchai Winichakul, give it a geo-body. The geo-body is the national territory within its borders and so it has a shape, a shape that rapidly becomes totemic, gets reduced to a logo, turned into a patch or a badge. People come to identify the nation with this shape and this shape with the nation, which is otherwise a pretty abstract thing. This makes the borders important, borders that exist first and foremost on the map. At the same time the map is this wonderful recordkeeping device. Borders, geo-body, recordkeeping: they keep reinforcing each other to magnify the importance of maps to the state which therefore imagines ever new uses for them. And so it grows.

LQ: Can we identify a similarly significant relationship between maps and the rise of other modern phenomena like science, colonialism, capitalism, or racism? Taking capitalism as an example, communal lands destroyed by a nascent capitalism’s enclosures were subjected to systematic surveys and boundary demarcations. When you mention the rise of well-defined state borders as taking place at around the same time, it seems to me that it’s following a similar logic of parceling. Can we think of a political world map as one giant cadastral survey, where all of the world’s land is parceled into property lots (that is, states), with governments holding the title deed?

DW: Yes, absolutely. This is exactly the situation. For the past 500 years states have ceaselessly asserted sovereignty over ever more territory. Today the only portions of the globe over which no claim is laid is a part of Antarctica and the open sea (and there’s surprisingly little of that). This follows explicitly from the territorial logic of the state. And no doubt the modern state, maps, and capitalism do evolve together. Your example of enclosure is a perfect example of one face of their relationship, though the reduction of national territory to a resource surface, as by the United States Geological Survey (or the Israel Geological Survey), is another. Here the goal is to ascertain, in the words of A. S. Hewitt, “What is there in this richly endowed land which may be dug, or gathered, or harvested and made part of the wealth of America and how and where does it lie.” Hewitt was the iron miner and smelter who, in 1879, wrote the legislation establishing the USGS. So, yes, the cadaster’s a big part of the story but so is all the land use mapping, the geological surveys, the mapping of the census, the soil surveys, and so on and so on.

LQ: The point you make about land use and geological surveys are dramatically highlighted in the West Bank where mapping an independent Palestinian state is becoming everyday more difficult. In the infamous “cantons” of Area A, where the Palestinian Authority has a highly qualified and circumscribed sovereignty, Israel retains control over the air space above and the sub-terrain below. Thus, as the radical Israeli architect Eyal Weizmann has written in “The Politics of Verticality,” none of us have a coherent map of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. And because of the tunnel/bypass scheme that connects settlements and villages to each other so Israelis and Palestinians never have to interact, under a “two-state solution,” we would have two states without clear contiguous territory. Would this configuration strip the geo-body if its meaning?

DW: No, the power of the geo-body is independent of a state’s shape or contiguity, though cool shapes make cooler logos and contiguous nations are easier to administer. But the UK hasn’t had a contiguous geo-body since 1801. The US hasn’t really had one since 1867 when it bought Alaska, and in no way has had one since Alaska and Hawaii became states. From 1947 to 1970 Pakistan was split by India. In the 1960s the United Arab Republic was split by Israel. Malaysia’s always consisted of at least two pieces. That Pakistan broke into Pakistan and Bangladesh, that the UAR fell apart, and that Singapore left Malaysia doesn’t speak to the geo-body per se, since there doesn’t seem to be any question that Northern Ireland’s going to remain part of the United Kingdom, that Hawaii’s going to remain an American state, and that Sarawak’s going to remain Malaysian. But these do suggest that like marriages, unions may not last forever. Island nations are generally another case. Whatever their territorial integrity their land masses are almost always discontinuous. Think about Indonesia. Yet its geo-body seems quite firm. At the state level, Hawaii’s another example.

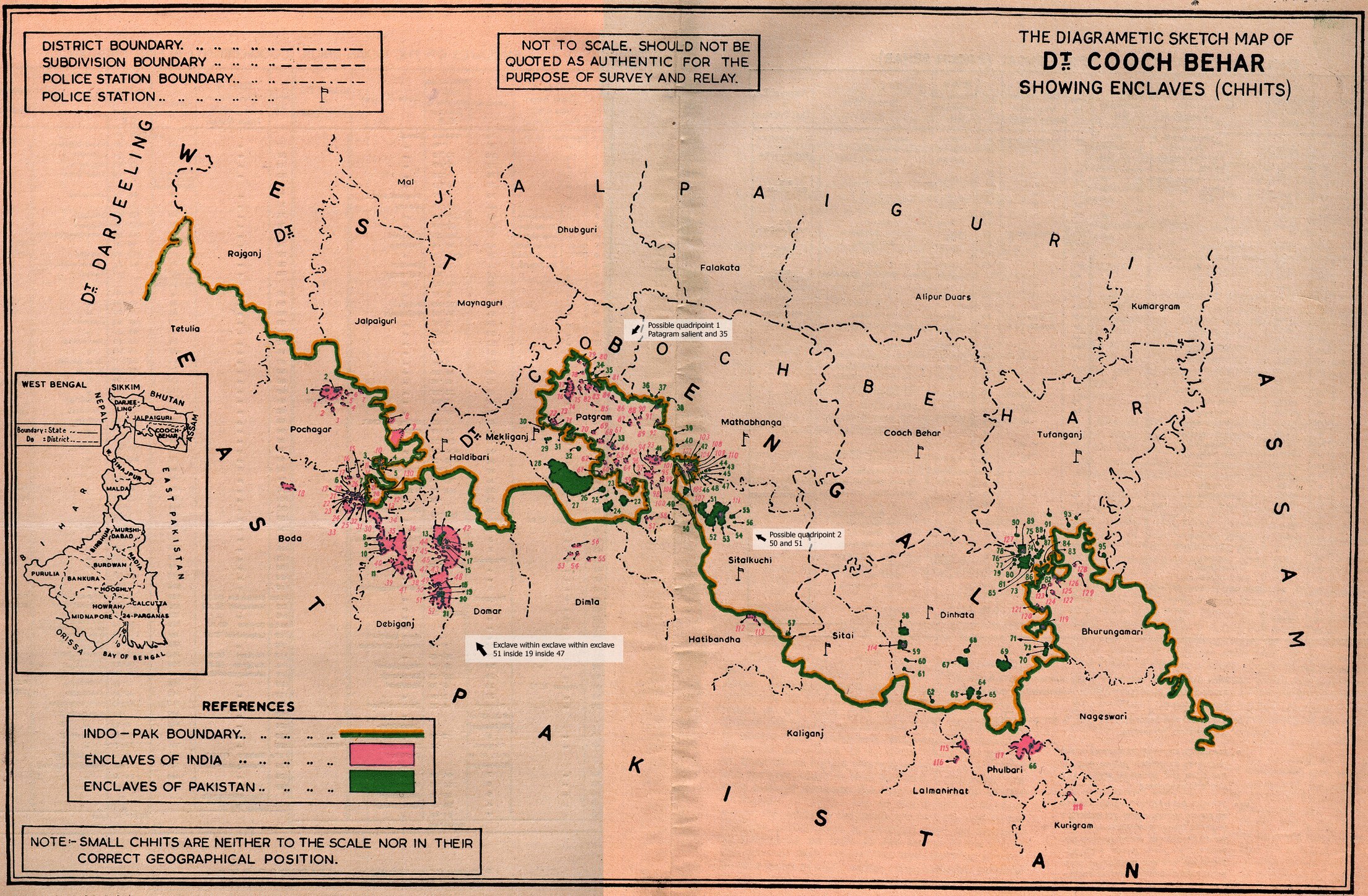

As for states worming over and under each other, this too is not unprecedented. Following partition, there were Pakistani enclaves inside Indian enclaves inside East Pakistan. Of course this only speaks to the insanity of the partition in the first place. More generally I’m thinking about how freeway construction splits neighborhoods which can remain connected through underpasses. Most neighborhoods break up under such pressure, though there are examples of others that continue to thrive. These freeways anticipate Israel’s apartheid construction in the West Bank, since typically it was white, middle-class commuters who were using the freeways to pass over poorer neighborhoods, often of color. There’s no question that class and race played key roles in the routes the freeways took through America’s inner cities. That some neighborhoods survived is no excuse, any more than that some island nations have strong geo-bodies excuses the shattering of the West Bank into an archipelago of Palestinian enclaves. I mean, why should there be any enclaves at all?

LQ: You often show that while violence is the ultimate force behind the map, the power of the map is such that this display of force is rarely necessary. How do societies get to the latter place?

DW: In nations with systems of courts, maps gain sway easily, almost immediately (though the reach of the court is established by the map). The map is a concordance machine. Mary Elizabeth Berry writes about the way in early modern Japan Hideyoshi used the very construction of the map as an “instrument of conversion” through which countless participants were instructed in the imagining of their country. (Simultaneously it was reduced to a cadaster.) Inevitably disagreements arise over borders, but once they’re negotiated, maps are generally respected, whether we’re talking about national borders, the borders of legislative districts, school zones, or floodplains, if only because it’s known that armed force stands behind them. Real problems arise only with states without borders like Israel where, because its borders have never been determined, the reach of its authority has never been agreed upon. States without borders have frontiers where their authority is diminished, ambiguous, or mixed. What Israel has is a frontier that extends to Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Egypt. This is the reality on the ground. It’s like the Western frontier in the US following the Civil War. Only the Palestinians are better organized than the Indigenous Americans were, and have achieved international recognition and, so though they have no border, they have a sort of proto-state. Before the recent reconciliation it was even more like the West, with Fatah and Hamas contesting each other’s authority. In such a situation maps have very limited authority and so less power. So the sorts of things maps resolve elsewhere here more often lead to violence. In this sense, of course, Israel is not a modern but a traditional state. In other senses as well (for example it’s a religious state).

LQ: The Nakba Day (May 15) and Naksa Day (June 5) protests this year, which breached Israel’s northern borders for the first time in the history of these commemorations, were met with deadly violence from the Israeli military. What does such an event say about the status and power of Israel’s map?

DW: Yes, of course we have to remember that legally Israel has no northern border. We need to insist on this. This means that the protesters no more than moved into a frontier region. That Israel met them with deadly force merely indicates, with respect to the border question, the level of its anxiety over its spatial legitimacy, the lack of authority, the powerlessness of its map. What the event demonstrates most sharply is Israel’s own awareness of its questionable legitimacy. Hence the violence of its defensiveness.

LQ: In Rethinking you mention that the use of maps without the need for force is aided by their connection with other organs of power — road signs, postal services, for example. Do these connections make maps all the more “real” or “truthful,” thus all the more powerful? Or is this about the state’s co-optation of people through everyday life, where we become committed to the system its map proposes – committed enough to defend it so the military or police doesn’t have to, I wonder.

DW: Well, as I said, the map’s a concordance machine, and anything that works to confirm the reality the map imposes helps construct that concordance, though you can see it the other way around as well, that is, that maps confirm the reality imposed by street signs, cancellation codes, addresses. There’s no chicken and egg here. It all grows together. In its infancy what the map did was systematize existing infrastructures, regularize naming, establish routes, to facilitate administration. Later it projected its systemization over newly incorporated territory, often within existing national borders, but lavishly over colonies. But in the end the only way it works is if everybody buys into it, which lots of people seem willing to do if only because it’s easier: “Well, that’s settled anyway.” In the end, that’ll be what happens in Palestine even though there will always be Jews who want everything west of the Jordan, and Palestinians who will never abandon their claim on the old home place in Jaffa. Why? Because with “that’s settled anyway,” people will be able to turn their attention to their kids, to their businesses, to their place in the international capitalist economy. Then, that’s when the power of maps will be unleashed.

LQ: A reason that Palestine/Israel makes such a great case study for your book, I think, is precisely because its maps are contested all of the time. The Palestinian struggle, even as the weaker military power, has refused Israel’s maps the luxury of hiding the State’s bloody origins. It seems here that both the map’s scientific accuracy and it military backing are not enough to allow it to unleash its power.

DW: No, you’re right. And you’re right to draw attention to the bloody origins. This is precisely what I was referring to when I spoke of the power of that Palestinian voice. But as I said, the real deal here is the fact that Israel has no borders. Until it does, it has no interior, it’s just one huge frontier where only frontier law prevails, everything is contestable, nothing is settled. In such a situation maps are powerless. The power of the map is to reduce the need for force, but that force is its ultimate warrant and, in this case, where the UN, Israel, lawless settlers, the PA, Fatah, Hamas, and other groups all contend, whose force is to underwrite the power of the map? It’s not like in China where, despite a border quibble here and there, it can claim, “This is an internal matter, it’s none of your business, butt out.” Lacking an interior, because without borders, Israel can legitimately claim nothing as an internal matter and though, conventionally, the international community is willing to grant that status to the 1967 borders, it really isn’t obligated to. And doesn’t. I mean, the UN is continually in Israel’s face about its actions and all over the Israeli occupied territories. Israel’s loss of status in the world, its declining standing, has become a reality the State of Israel can no longer pretend to ignore. It’s becoming a threat to its existence … in any form. Increasingly Israelis recognize this. They know they need borders, if only to allow maps to work their magic.

Earlier you asked if we could think of a political map of the world as a giant cadaster where state governments owned all the property, and I said we could. Well, there’s a limitation to the analogy. Property rights are guaranteed by governments, but where states are the property owners who writes the guarantees? No one, in fact. It’s mutual respect or war as our recent history has made only too plain. Well, Israel is losing any respect it had not only because of the way it treats the peoples whose territories it occupies, but because of its signal failure to establish real borders. Real here has a simple meaning: borders everyone in the community of nations respects. What other nation in the modern world has so intransigent a history? Korea?

LQ: Having real borders is such a strong legitimizing force in the international community now, that many dispossessed indigenous movements themselves have attempted to work within that framework. There’s a famous response some anti-colonial cartographers have identified with that says, “more indigenous territory has been claimed by maps than by guns; thus, more indigenous territory can be reclaimed and defended by maps than by guns.” But when I hear this sentiment, I can’t help but to imagine the White Man bopping the Natives on the head with a rolled-up map until they succumb to his right to exist on their land.

DW: Well, of course it’s nonsense. It may be that more territory was claimed by maps than guns, but it was the guns, or the threat of guns, that turned the claims into any sort of sovereignty. What the crack – it’s Bernard Neitschmann’s – overlooks is the fact that no map does anything at all without the implicit threat behind it of armed force. As for the reclaiming, it will only be accomplished in the colonizer’s courts, which have explicitly the force of law behind them. And at that, it’s a limited sort of reclaiming.

LQ: Something you’ve shown, that will probably surprise many Western scholars and activists on Palestine issues, is that despite its attractions, pre-modern maps of Palestine are all but nonexistent. This is quite extraordinary, seeing that Palestine has been such an important place to the three monotheistic faiths for millennia—and of course, it is important for so many today. Indeed, today the conflict is difficult to talk about without looking at not just one but several maps. The modern mind might interpret the lack of maps to mean that Palestine was not important until the West decided it would invest resources to survey it.

DW: Well, it wasn’t important. And the West’s mapping it didn’t make it important either. Palestine was an Ottoman backwater that attracted attention, if at all, only because of the holy sites in Jerusalem. Constantinople was important, Cairo, maybe Damascus, but the Ottoman Empire consisted of 29 provinces and numerous vassal states. It embraced Bosnia, Kosovo, modern Turkey, Syria, Lebanon. I mean, what was Palestine in this? Or on the world stage? Not much. This is absolutely not to say Palestine didn’t exist – and as such – for as far back as you care to go. But important? To whom? And why? It was so insignificant that the British didn’t think twice about giving it to the Jews.

And of course the most important survey the West carried out, under the British Mandate, was by way of facilitating its transfer to Jews. What made Palestine important was its invasion, its colonization, its conquest, its occupation by European Jews, and the Jews’ murder and expulsion of the indigenous Palestinians. Unlike the situation that prevailed in 18th and 19th century America, when Europeans did the same thing to the indigenous Penobscot, Shawnee, Iroquoi, Cherokee, and so on, in the 1940s the international press was on hand to document and broadcast what the Jews were doing to the Palestinians, the UN was on hand to register the refugees, and neighboring Arab states were open to receiving them. And over the years the Palestinians have insisted, in an ever stronger voice, on their right to a place in the world that they can call their own. That’s really what’s made Palestine important, that persistent Palestinian voice that has insisted on Palestinian importance, that has drawn attention to itself, that has refused to allow the world not to listen. It’s the Palestinians that have made Palestine important!

LQ: “Where talk serves maps are rare,” you write. What was it about Palestinian society’s social configuration that didn’t call for mapmaking?

DW: Well, nothing unusual or peculiar. Traditional societies never called for maps anywhere in the world. Everybody knew who had what rights to what resources. I don’t want to paint an unduly rosy picture here – doubtless there were disagreements that often led to bloodshed (as happens just as frequently in modern societies with law courts and police forces) – but life was lived in comparatively small communities and common knowledge was common coin. What would you need a map for? It’s only when relationships get abstracted (distant landlords), or contentious (and where distant courts are involved in resolutions) that maps are called for. You need maps to convey locative information over distances or across generations in the absence of other transmission mechanisms. Under the Ottomans the Palestinian situation was complicated in that at the local level it was a traditional community with a rich assortment of tenure conventions, common land, and so on; whereas at the Imperial level these communities were in some sense the “property” of wealthy Ottoman overlords. Mediating the local and imperial were rent and tax farmers and their ilk. In such a scenario the only place maps could conceivably be called for would be land transfers at the imperial level, and no transfer document has never required a map.

LQ: Do these histories stand the danger of being erased each day we see more and more maps utilized in the struggle?

DW: Yes, certainly. The old world is over. Even assuming a happy outcome, nothing will revert to the way it was. Everything will be mapped (has already been mapped!).

LQ: You describe counter-mapping as important but also as “reactionary.” This is a term I usually think of to describe a politics where the oppressed adopts its oppressor’s conceptual framework. In the Palestine/Israel case, for example, the fight is over the content in the map (place names or border placement, for example). But the map itself as a tool for conceptualizing space is not at all in the debate. Should the conceptualization itself be a question that’s up for discussion?

DW: I’m not sure we’re on the same wavelength here. I have a much broader conception of reactionary than you seem to, and certainly don’t limit it to politics as such (though I acknowledge the political force of all action). As I crucially experienced it growing up, it derived from a fear of being shunned or laughed at that manifested itself either in straightforward conformity or in difference for its own sake. Kids who dressed “like everyone else” for fear of standing out and kids who wore what they did just because no one else did equally struck me as having little interior life of their own. Since neither was forging his or her own path I found them equally reactionary. I’m certainly not immune to such feelings. When I go to an AAG meeting [Association of American Geographers] and see all those people in suits – all those pompous jerks – it makes me want to not merely wears jeans but, you know, to shred them and wear studs. Now that’s reactionary! Especially since the mere thought of having metal penetrate my skin turns my knees to jelly. But it’s just …. God! I don’t want to be like them. Okay, wholly reactionary.

So in the case of Zionist mapmaking, where they didn’t just create a Zionist map of Palestine, which would have been nasty enough, but explicitly created an anti-Arab map, that was purely reactionary. It wasn’t mapping. It was explicit counter-mapping. The Zionists didn’t build a place for themselves so much as systematically erased the existing one. It was as if they were afraid not of the other kids in the cafeteria laughing at them, but of the ghost of the Arab world they were expunging haunting them, driving them mad (they all knew – you can tell – that they were doing something vile).

So maps that are just against other maps, they strike me like high school Goths dressing in black. Or “professionals” wearing suits and ties to make sure you don’t mistake them for “workers”. So when Palestinians make explicit counter-maps, they strike me as no less reactionary than the Zionist maps, even though I think the Palestinian maps are more or less on the side of the angels. In the end there’s little enough interest in the maps. Still, it’s important they be made if only because maps are an important channel for the voice of Palestinians to make itself heard. Abu Sitta’s Atlas of Palestine 1948 is a monument in this regard, though ultimately it’s merely a counter to the national atlases of Israel.

Far more interesting in this regard is the Subjective Atlas of Palestine which I don’t think is the least bit reactionary. The Subjective Atlas of Palestine is like the kid in high school who forged his or her own way regardless of derision. It bubbles up out of the rich interior life of Palestinians without caring about what most people think an atlas should be and with supreme disregard for Israeli maps. I love this atlas. I should say, though, that originally, that is, when Mercator named his labor of love Atlas, while maps were to be a part of it, it wasn’t about the maps. Mercator’s Atlas was to be a cosmographic meditation on the “Fabric of the World,” in which maps were intended to play little more than the part maps play in the Subjective Atlas of Palestine. In fact, there’s a long tradition of books called atlases that have no maps in them at all. Very often they’re albums of drawings, anatomical atlases, for example, though they can be collections of photographs or paintings, like Gerhard Richter’s Atlas or Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas. The Subjective Atlas of Palestine is very much in these traditions, an album of images of Palestine – traditional dress, food, faces, tiles – with some maps; most remarkably, despite ample provocation (and sections on the lack of a currency, passports, and prisons), not anti-Israel but bracingly and embracingly … for Palestine. It’s a beautiful book that supremely exemplifies non-reactionary mapping, for despite the paucity of maps, it certainly maps Palestine.

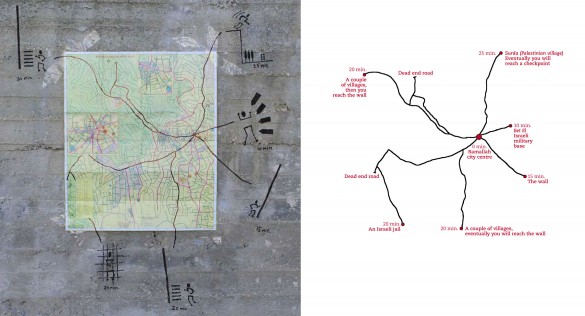

When it uses maps, too, it often uses them in telling ways, not to contradict another map, but to reveal something important. So, a map of the extremities of Ramallah: down this road, the wall; down this road, an Israeli prison; down this road, the wall; down this road, a checkpoint; and so on.

What a wonderful book!

Denis Wood is an independent scholar writing critically about maps for the past four decades. His recently published Rethinking the Power of Maps (Guilford Press, 2010) argues that the rise of the map coincided with the rise of the nation-state, and uses Palestine as a case study to illustrate how maps only come into existence when societies call for them. In this interview, Wood elaborates on this idea by discussing the history of the modern map, its role in society, and the violence underpinning their use in Palestine.

Linda Quiquivix is a doctoral candidate in the geography department at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She is currently conducting research on a dissertation entitled The Political Mapping of Palestine.